Chapter 8 – La Merdaille

November 1381 – March 1382

"Smite a villein and he will bless you; bless a villein and he will smite you"

– Barbara Tuchman, 1978 (A Distant Mirror, p.175)

Devereux's Folly, culminating in the Battle of Southwark, is often recognised as the end of the first phase of the English Revolt. With the Captain of Calais's fall on the battlefield south of London went hope that many of the old ruling class had that this whole mess of could be reversed, the natural order reinstated, and things could once again go back to a relative sense of normality. God clearly had other plans, as the victory was interpreted by Tyler, Ball and the other revolutionaries now in control of England. "God has spoken, and said that there should be no gentleman nor villein in England" Ball preached to Tyler's soldiers in the battle's aftermath.

Devereux's and de Treseguidy's men found that their defeat was not the end of their suffering. Tyler's army knew that there were French knights among the captured enemy. When seeking them out, they would haul a man aside and ask him to say the words "bread and cheese", if he replied in French then he would be taken away and beheaded. Sources differ, but estimates state that from the roughly 500-strong French contingent, over 300 were massacred and several heads were placed on spikes on London Bridge. To the new leaders of England, the Frenchmen were seen as just as much an enemy of the people as Sudbury, Hailes and Gaunt were, and the treatment visited upon them was little better than that visited upon the Flemish weavers of London in summer [1].

Six months on from the initial outbreak of violence in Essex, much had been achieved. The old pillars of governance and the feudal social had crumbled, yet there was still little pre-determined planning as to what to do next? Informal and

ad-hoc arrangements had been responsible for much of the change outside of the south and east prior to

Carta Communia, and there were few ideas on the constitutional means of moving forward. Prior to Southwark, most work centered on tying off loose ends and appointing new officials to vacant offices. Kempe had been appointed to fill the role of Archbishop of Canterbury on October 21st. Soon after, a new Treasurer was appointed - Robert Sutton, the former Lincoln Mayor and now budding revolutionary. As a wealthy merchant, he had prior experience of handling money and was considered a safe pair of hands. Robert Moore [2], the Cambridge lawyer was appointed to replace the deceased Sudbury as Keeper of the Great Seal, with the powers of the office of Lord Chancellor but without the aristocratic-sounding title. For that matter, other offices of government had "Lord" dropped from them, such as Sutton who was merely titled "Treasurer". Finally, Tyler himself had the old office of "Justiciar" resurrected with himself as its holder [3]. Rather than head of the King's Court, as the office had once entailed, Tyler held this new iteration as a regent for Richard II during his minority. From a roofer in Kent to

secundus a rege - second from the King [4]. Richard himself still held little power in his own right, effectively passing from one regency council to another. It was little comfort that his new councilors referred to him as "

Richard, second of that name, father of the English and king of a free people" in

Carta Communia [5].

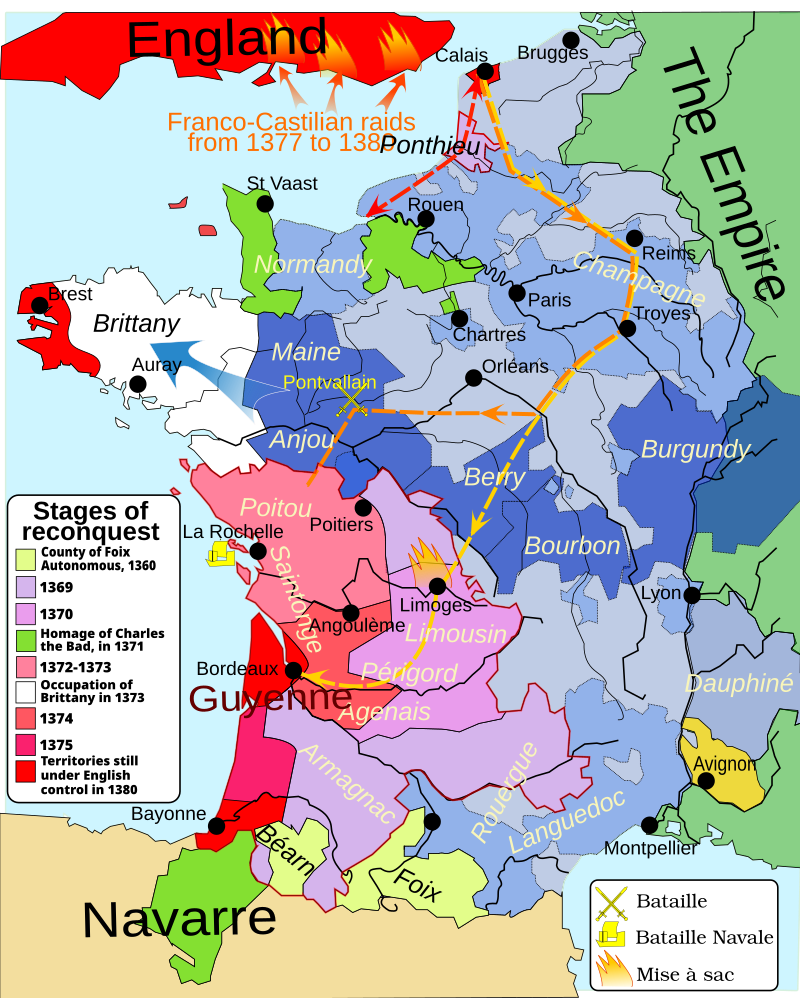

The Kingdom of France was the most powerful state in continental Europe to react to the English Revolt, and the second overall after Scotland. News had filtered across the Channel in the weeks after the rebellion's start. Whilst concerned, the French regency had paid little attention to it out of a belief it would eventually be repressed. When it was clear the revolt had not been suppressed, and had instead grown more radical and widespread, the French court began to panic as memories of the

Jacquerie came flooding back. This was why they had sent de Treseguidy to England alongside Devereux in the hopes of finishing the rebels off themselves and then extracting political concessions from the restored English court. The army that Devereux and de Treseguidy met at Southwark had not been the mob of the summer, but had developed into a well-armed and combat experienced force that drove the counter-revolters from the field.

Alongside developments in England, the defeat also had ramifications on French politics. The three Dukes serving a regents for the young Charles VI - Anjou, Burgundy and Berry - became extremely worrisome. What would come from this? What of the knights and their accompanying entourage, what was happening to them? There were worries that French commoners would rise up as well, that the chaos and anarchy that was gripping England would find its way across the Channel, maybe even through the English possessions in France. As November turned into December, the arrival of a new Captain in English Calais brought panic among the regency in Paris. There was talk of raising an army to besiege English holdings for the sake of preserving order in their own realm.

There was a problem with doing this, the country was in dire financial straits as it was. In 1380, King Charles V had repealed the hearth tax [6]. This sudden releasing of the tax meant that the war effort could no longer financially sustained. To restart the fight would require money, money the government currently did not have. There was no other realistic choice but to reinstate Charles V's old taxes, risk-fraught though that was. For all their bickering, the three Dukes worked out a plan for 1382. They would take the fight to the English, and then put the lower orders back in their place. Across December 1381 and January of 1382, the Dukes summoned Parisian representatives and were "

convinced" to accept the reimposition of the salt tax and customs duties. Tax farmers were appointed as news gradually seeped out to the French public [7]. They had also heard some news of events in England, and whilst they had no intention of directly supporting the English enemy, there were some who were hopeful. If the English could bring their corrupted and ungodly lords to justice, surely they could bring theirs to heel as well. Especially as those magnates were intent on reimposing their hefty taxes, had they not suffered enough?

The news of the taxes was recieved about as well as could be expected, with the first outbreaks of violence erupting in Rouen in early February 1382. On the 6th, a local draper named Jean le Gras stormed the cathedral and began tolling the bells. Elsewhere in Rouen, others closed the city gates and began to fill the streets [8]. The violence in Rouen was not quite as brutal as the violence over in England, but much property was destroyed. The rich, the tax collectors, churches and town councilors were targeted specifically. Like in England, the Roeun rebels began to search for public records, destroying paperwork containing records of debts and rents. Another group of rebels descended on the nearby Abbey of St. Ouen, recovering their 1315 charter - granted by King Louis X - and destroying the gallows [9]. When news reached Paris of the rebellion, the court fell into panic. The Duke of Burgundy left Paris for Rouen with a small army, leaving no armed force to keep order in the capital.

After two day's absence, Paris also fell into revolt. A mob of roughly 500 descended on the tax collector's offices. The mob grew into thousands, and began raiding the Palace de Grève for weapons, and then proceeded to loot and burn churches, wealthy homes, government buildings and the Jewish section of Paris. Riot quickly turned to pogrom as hundreds were killed and the deceased had their children forcibly converted. With no force capable of meeting the rebellion as chains were hoisted on the streets, preventing de Treseguidy - back from England - from restoring order, the royal government left Paris to meet the returning army [10].

The King and the returning army reached the gates of Paris by March. The Duke of Burgundy rode forward to negotiate, finding the rebels inside had three demands:

1. Abolition of all royal taxes

2. Release of prisoners of the Duke of Burgundy

3. Amnesty for all involved in the rebellion [11]

At the same time as negotiations were underway, the Duke's army seized strategic posts overlooking Paris, cutting it off. Agreeing to release prisoners, he nonetheless refused to agree to any other demands. That night, the city was taken under control of the Parisian guilds, who still kept the gates firmly up.

As news spread of Rouen and Paris, the rest of France erupted into violence, excluding Brittany, Provence and (ironically) Burgundy, where the French crown had no powers of taxation. This also meant no money to raise an army to suppress the revolt. With no other choice, the King and his council agreed to negotiate with the rebels. After agreeing to grant amnesty and repeal the taxes, the Parisian gates were reopened. Afterwards, the rebel leaders were rounded up and executed. Paris were secured, off north to deal with Rouen - which was surprisingly easy as the Norman city opened its gates with no resistance. The revolt's leaders feared execution, and they were right to. Most of the city's rebel leaders were executed in the aftermath [12], the city's charter was revoked and the church bells confiscated. With Rouen secure, much of the rest of France would fall back in line. The Harelle, as the rebellion became known, was a major scare to the French leadership, who would spend the next few years restoring order to the country and eliminating their opponents. Their would still be action to tackle the revolt in England, of that the French leadership had no doubt, but for now it would have to wait.

Southwark had been a scare for the English revolters in many ways. Not only had a foreign power involved itself in attempting to overthrow them, but English aristocrats and other notables had also joined with Devereux and de Treseguidy - in Kent, of all places. There had been fears among some of recalcitrant aristocrats and notables who would betray the revolt, Devereux's expedition had merely solidified those fears. Although hundreds of miles away, John of Gaunt would become the namesake of these supposed enemies, and the attempts made by the new ruling class in London to root them out would turn into one of the darker chapters of English history, the Kentish Purge.

Footnotes

- [1] The Flemish population in London was targeted by the revolters in OTL as well. They were seen as exploiting the common English people and were killed, the phrase "bread and cheese" comes from OTL as well. One of the revolt's darker episodes.

- [2] Sutton was a real person, and a powerful and influential one at that, whilst Moore is fictional. Both have been mentioned elsewhere in the story so far.

- [3] The office of Justiciar was abolished in 1265, it's last holder being Hugh Despencer who was killed at the Battle of Evesham.

- [4] Tyler has effectively made himself England's chief minister here. Though he isn't all powerful due to the nature of medieval politics.

- [5] A similar style of address was given to King Louis XVI of France during the early phase of the French Revolution.

- [6] Charles did this in OTL. No one really knows why though.

- [7] The tax reimposition happened in OTL as well, although for different reasons and here it has been brought forward slightly.

- [8] This is how the Harelle uprising began in OTL as well, although butterflies mean the timing has been brought forward by a few weeks.

- [9] This happened in OTL as well. Recovering their local charters was very common in medieval rebellions, and it happened in England in 1381 both in OTL and here as well.

- [10] Much of this is lifted from OTL.

- [11] OTL demands of the Parisian rebels.

- [12] In OTL, only 12 Rouen rebel leaders were executed. Here, the French government's perception of instability given the events across the English Channel causes a more hardline response.

Sources

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org