Huh, those Lancaster men do like taking an arrow to the face and getting away with it, don’t they?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

To Delve and Spin – A Medieval English timeline

- Thread starter BurkeanLibCon

- Start date

Certainly beats Richard I.Huh, those Lancaster men do like taking an arrow to the face and getting away with it, don’t they?

Really enjoying the TL so far! It's a really interesting scenario,very well written and clearly very well researched. Keep it up!

(Just wanted to give some positive feedback since this work deserves much more of that than it's getting )

)

(Just wanted to give some positive feedback since this work deserves much more of that than it's getting

This is great. I love the pictures and the footnotes also. Adds to it even more.

dcharles

Banned

maybe burning Gaunt's precious gold and gems had been misguided

This is the second reference to this that I've seen. You do realize that you can't incinerate most gems, right? They're rocks, after all. And gold just melts. It's still has equivalent value.

Other than that, this is great. Have you ever read _Summer of Blood_, by Dan Jones?

Congratulations @BurkeanLibCon our author, for what I take to be a pretty original or anyway unusual opportunity in history for an ATL branch, and making it quite lively!

I have always thought the Peasant Revolt with its motto ending "who then was the gentleman?" was pretty inspirational at least in potential, and its OTL ending in royal treachery and murder and general terror both a more than adequate retrospective justification for just about anything the peasants, Tyler, Ball et al might have done that was unfortunate--and a macabre and apparently (for half a thousand years and more anyway) eternal sneer by the victorious elites at the thought of human equality. Picture a boot stamping on a human face, forever, indeed. So, glory becoming tragedy ending in farce and bitterness.

I do have some high hopes, perhaps to be dashed with just as much historic irony as in OTL at some later point, that things an uptimer progressive minded person like myself would call good do come of all this!

However...

But in that case--well, a positive glow over an idealization of the pithy spirit of "When Adam Delved and Eve Span, Who Then Was the Gentleman?" is as I say certainly something I for one like, along with such cries as "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" or "As He died to make men holy, let us live to make men free" or of course Lincoln's "government of the people, by the people, for the people."

That's my own idea of glory--to quote a less famous and more ambiguous and ironic song (titled "Marat/Sade" and sung by Judy Collins in the version I know) "...screaming in language that no one understands / of the rights we won with our own bleeding hands/ when we wiped out the bosses and tore down the wall/ of the prison they told us would outlast us all..." That's glory--but the song is about the long term apparent failure--"Marat, we're poor/and the poor stay poor..." which is why the "new generals, our leaders anew" are appropriating the claims of the Revolution, but mocking its content while they "sit and argue, and lie upon their backs..." And why the Marquise de Sade, himself an imprisoned inmate in a Napoleonic lunatic asylum, is putting on this play which ends in the insane cast members mobbing the gentry audience.

At the end of the day, unless the English somehow find a radically different path and one that conventional wisdom dismisses as downright impossible (I don't, but actually achieving anything close to what I'd like to see is clearly hard work and quite likely to fail in the attempt, perhaps not without some long term gains to be sure, though perhaps just as likely or more so, long term damage as well) then England must return to the mainstream path of European development, which means the question of who the Gentlemen were at the dawn of human prehistory is as moot as ever, because we've got new ones now, and their power has a basis. Any success the common people have in uplifting and maintaining their dignity and rights and a place at the tables of power derives from their sacrifices and great risks they run struggling for it, and the ability of their descendants to sustain and maintain their place in the face of new challenges and new opportunities for a few to seize or quietly accumulate power over them as circumstances continue to change. People committed to ideals of modern era humanism including political equality do well to be inspired by the struggles of the past, and even to ignore, or better yet heed and maneuver around, the tragedies of their defeats, but actually it is their integrity, their solidarity, and their prudent actions here and now that really matter, here and now.

They aren't likely to want to be Odonians after all, though honestly I do think the notions of free voluntary contribution to the metabolism of a scientifically understood "social organism" are actually closer to what late High Middle Ages English peasants would want and after thought and deliberation, accept and understand and maybe just perhaps manage to achieve, than the ideals of the liberal ages.

At this stage of human development, the vast majority of the nominal subjects of Richard II, be they the rebels now paradoxically sworn royalist loyalists, reactionary old regimists like Gaunt and the men they either inspire or dragoon into their hard-line aristocratic opposition, or people just trying to keep their heads down and out of range of swung scythes and swords and arrow crossfire, are peasants living in little villages and out-dwellings in the shires who mainly want to be left alone.

If we could have true democracy among these people at this time, what they would demand is massive devolution of government power into their own small scale hands, exercising justice as they see fit, and sadly I fear all too likely to respond to a much lighter aristocratic/royal hand by feuding with each other, at least marginally (mainly, they need to work terribly hard in the hope they might feed themselves adequately over the course of the next few seasons and not look much beyond that)--and of course if they had their way completely, there would be no royal taxes whatsoever, no dues to any gentry, and perhaps not even a very humble and hand to mouth priesthood nor a church--they might want church in the abstract, but would they freely and voluntarily pay to sustain what they expect a church to give them, in material terms?

As for mythic and transcendental nourishment of the soul--again they might actually miss some of what their hitherto traditional churches have been offering them, in sermons, stories and the stained glass window and sculpture illustrations of the medieval take on the Bible and tradition, but they might also find push comes to shove, they can supply enough of that to suit themselves by telling stories and doing some rituals on a volunteer basis. They might or might not then choose to maintain someone as a designated priest, but would they need to accept someone alien to them sent down by some distant bishop, or wait on the approval of one of their own by that same bishop, or miss any training village priests actually got in the old regime that might be lost?

Certainly if we look across the Irish Sea, the early Christian era of Ireland does suggest that such peasants as these English ones might well indeed, on a voluntary basis more or less, sustain a hierarchy of monasteries and look to their clerics for wisdom and judgement.

But meanwhile--could such a peasant confederation of essentially separate villages, far more decentralized than the Heptarchy at its most scattered into tens of thousands of small parochial communities, possibly survive in the late 14th century with the Kingdom of France and the outlying Holy Roman Empire possessions of the Low Countries not to mention the ambitions of kings in places like Denmark all lying just across the Channel and North Sea, and with the still traditionally late feudal kingdom of Scotland right there on the land border (nor have we quite dealt, at this early stage of the author's story, with the situation in Wales yet)? Those likely predatory enemy regimes do command somewhat centralized, somewhat disciplined, relatively expensive armies they can pay for because of ruthless ongoing extortion of their own peasants, just as the dynasties descended from the Norman conquerors in England had in England only yesterday here.

One thing I have lost track of is how much land, and where, on the Continent, was prior to the revolt practically under English rule--certainly any such domains in France would also have the King of France at least claiming suzerainty over them. IIRC a major reason King John in the previous century had to come to terms with his barons at Runnymede resulting in the original iteration of Magna Charta was that his maneuverings brought him to a debacle where he had to sign over all lordship over anything in France back to the French king, in toto, so for a time anyway England had no foothold on the Continent whatsoever.

Now I gather that somehow or other, I forget how and why and where, later kings of England managed to get effective lordship in places like Gascony back into their hands, presumably dynastic marriages were a big part of how it was done, and later OTL of course they surged into France on a massive scale and grabbed control of quite a lot, eventually getting to the point of the later French king surrendering all his domains to the heir of Henry V (whom I suppose is pretty well butterflied away completely already at this point in the ATL narrative).

Meanwhile "now" in the narrative, it is possible these overseas English holdings in southwest France and wherever else they might be have not even yet gotten news of the events of the revolt, but if not they will know about them soon. Just as the English barons were disgruntled and angry and backed their nominal King John into a corner because they had lost their revenues and ties (at least some of them might well have been born and raised in the demesnes now lost to them in Normandy) so many of the lords on the mainland will not take the loss of control of their holdings in England lightly, and will respond to a call to rectify matters by restoring a version of the old regime in England--and might well agree to considerable setbacks in their power and claims in England and even in France to get just a part of their English claims back. And therefore for instance come to terms with the King of France, or perhaps some other adventurer such as some delegate of the Holy Roman Emperor, or some Scandinavian king, to join forces with them to invade by sea.

Can England, even if we were to make little of the further hurdles the Tyler-Ball led movement, and figure Richard plays a most useful role in tying together a new regime fast, hope to defend itself by sea alone?

Well, of course the English lean more heavily on navigation than the average 14th century northern European nation does (maybe not more so per capita than say the Norwegians or even Danes, but of course those two branches of the Danish crown lands have rather low populations versus England; the Flemings, with the proto-Dutch a peripheral backwater to their north, have considerable investment in shipping too). And for that matter as anciently as the reign of Alfred the Great, and with only half of England in his control at that, England did muster a substantial navy.

But in this era, we are still pretty far away from the concepts of modern sea power after all. To begin with modern naval warfare is defined by firepower and the ability of warships to either repel, evade or endure heavy shelling/bombing; in this pre-gunpowder era (well I think it is just starting to emerge in European warfare, but at the very beginnings) a naval battle, such as they were, is either a matter of ramming enemy ships to sink them, or grappling with them so the two ships' crews can fight it out hand to hand.

Also and very importantly, navigation itself is still pretty primitive, and ships generally don't go exactly where their pilots and helmsmen might wish them to go; chance is a huge element and fleets are pretty hard to keep together, tending to be scattered and wind up at various somewhat random destinations.

Alfred's "navy" then, and IIRC Harold of Wessex had one up and running hoping to have some defensive effect, was a matter of coastal patrol at best, and could reasonably be expected at best to give some early warning of an incoming invasion fleet, with good luck anyway, and perhaps to attrit or divert such an invading armada, if in fact the English could maintain enough hulls diverted to such armed defense, which is of course a major drain on the royal exchequer or alternative paths of funding, while removing the hulls from the useful business of trade. (In this era and for some time well into the early modern one, a good warship was largely interchangeable with a decent merchant ship; a navy was largely a militia of merchant hulls and crews carrying warriors instead of revenue cargo, with some more specialist ships such as galleys in the Mediterranean being the warships as such, but in northeast Atlantic waters such vessels were not much favored!)

Richard can't rely on "wooden walls" alone to keep the peace for his landlubber peasant subjects then; the kingdom requires some kind of army, and one numerous enough to stand ready to fight and defeat major landings anywhere the combination of invader plans and the fate of fitful winds might bring them on the English coasts.

This is assuming of course that whatever armed forces Richard can maintain in the name of his restive peasant subjects are not engaged up to their necks in hard fighting of yet more reactionary gangs in various remaining strongholds, say in Wales (where mere reaction in favor of the old Norman style aristocratic regime might merge or clash with revived Welsh proto-nationalism seeking to set up a new Welsh kingdom or possibly some kind of republic, Wales for the Welsh (Cymru I suppose, by this late date, would be the actual name would it not?) Conceivably, if the spirit of the Peasant Revolt has spread organically to Cymru lands as well, a parallel Welsh regime might come to reasonably mutual agreeable terms with a strictly English one, if Richard is prepared to agree to relinquish control over lands some English king or other has more often than not controlled for centuries--but even with a truce in place and an amicable divorce, such a Cambrian regime might find it expedient to ally with Richard's continental-backed foes, and even when it seems relations between London and Cardiff (if that is where a Cambrian court would settle, in this era I suppose it might be in a lot of other places instead) are pretty good and the "Welsh" interest seems to harmonize well with the English one, still some kind of garrison border defense would have to be kept up in place by any prudent English regime--a diversion of strength a king of England who is in this position of having to placate common mobs because the most expedient taxes his ministers could imagine were the trigger of revolt, in particular then, can very ill afford. Far better if Wales falls into line, even if it means special concessions, and its defense is incorporated--but can Richard, ruling for the moment by consensus of a peasant mob, manage to do that when he couldn't even forestall this mass rebellion of English?

Then of course there remains Scotland to the north, for the moment anyway not facing any peasant revolts of its own, though perhaps that could change, which has allied with John of Gaunt once already--and got their clock cleaned to be sure, but sending the Scots back to Scotland is one thing, deterring them from striking again, and again, and again whenever they think it expedient, is something else.

The author has already dropped the hint that the conservative armies have a distinct per capita advantage of relative established discipline and professionalism of a sort, in remarking how they suffered a lower rate of attrition than the Peasant-Royal Loyalist alliance did. In part it was just that the latter had marginally higher numbers, and mainly that they had better luck, that bought the new nominally royal actually rebel commonwealth some further breathing room and time.

Of course presumably, the more battles the ragtag Loyalist, if I can call them that, forces fight, the more their forces will tend to find ways to get their act together tactically and strategically, and eventually they will be overall a match for traditional late medieval forces.

Indeed we might imagine ways they might stumble into surpassing them, if forces raised from more or less voluntary levee en masse peasants will learn and accept appropriate kinds of self-discipline and turn spur of the moment wiles into consistent battle doctrines. Already on the Continent IIRC pikemen have developed in the Low Countries and perhaps elsewhere, like Switzerland maybe by this date, to check the pretensions of mounted knights, and at all stages foot soldiers have never been completely eclipsed.

Meanwhile even the Normans--one might say especially the Normans, with William the Bastard/Conqueror keenly aware of the need to keep his Norman and Flemish barons under as much central control as he could manage--built on or reinvented older English traditions of fairly central, at least in theory, loyalties of royal forces, and reinvented over time a semi-consensual balance of power between monarch and dispersed local power with an eye to realm unity and general domestic peace while standing ready to either repel invaders--or invade in their turn. It is entirely possible this political revolution, if it can consolidate and establish a track record of more military success, might foster both significant social transformation, either streamlining away hereditary nobility completely or anyway anchoring English lordship again to a continuous national regime served by a unified (if somewhat dispersed) army.

But if the peasants are not to suffer the same fate as OTL just a few years later if that, such an army has to lean on the villages themselves agreeing to shoulder the burden, to pay considerable sums of wealth in some form or other to sustain the forces, land and sea, and to allow their own sons (and daughters, there are always a few women sneaking into nominally all-male forces, generally by disguising their sex) to be taken off to be drilled up into soldiers and often never return, either being killed off or winding up settling into life somewhere far away. Meanwhile the crops still have to be grown, peasant industry still has to be performed. Perhaps indeed they will sacrifice far more for a kingdom they see as their own, with its fighters fighting to protect their own peace such as it is, than they were willing to see extorted by haughty overlords. But how much margin do they have before their villages collapse into famine anyway?

And of course the actual composition of the forces that did repel Gaunt and King Robert of Scotland was by no means entirely some New Model Army 14th Century Edition composed entirely of patriotic peasants. No, their leaders, even the most grassroots and unpretentious of the lot, were veterans of the older wars, and in fact we have some Gentlemen of the old school expediently allied to them. Clearly there will be limits to the general consensus and amity of such mixed forces, however successful they might prove to be in repelling invaders and suppressing diehard conservative opposition.

Who now is the Gentleman? Well, King Richard to start with, and however much intelligent peasants might thrill at the idea he is a divinely ordained King of the common people (certainly anyone literate in Latin, or getting ahold of a wildcat English Bible, can draw and expound some inspiration from the Old Testament here, though certainly the Book of Samuel itself contains the warnings of that very prophet that the Children of Israel would regret setting up a king, be he Saul--or David for that matter; it's a bit of a two-edged sword ideologically speaking!) in fact Richard is the child of late Norman legacy nobility, and surely sees himself as much as the first lord among a distinct and superior lordly class as he might be flattered to be told he is also separately the King of the smelly and ignorant and properly submissive commoners.

Then we have other fellows quite as noble as Richard also marching for the moment to what must seem an awkward and dangerous cacophony of different peasant drums--how soon will be, if ever, they reconcile themselves to a less lofty social role, with fewer or in theory no divisions setting them well above the common masses as special men set by God to rule these sweaty and dirty sheep, and to appropriate their hard work in luxury and power as a matter of right?

But the mob can hardly turn on them and hang or otherwise massacre the lot of them just yet, and expect to survive--and since in fact the mob really is composed of shrewd, intelligent people who can see the realities they face, they won't be too careless just yet either and go on stringing their nominal lords along, and perhaps hope for some kind of easy settlement in the sweet bye and bye.

Now suppose England manages to square all these circles and a fairly secure and consensual regime does emerge, with Richard II having the wit and integrity to stay perched on top and his council however eclectic capable of hammering out policy after policy the villagers (and townsfolk, I haven't mentioned them because they are a minority, but they sit at some pretty crucial junctions of power and are definitely players in this game too) will accept and support.

What is England's larger geopolitical situation, aside from the specific obsessions of old regimist conservatives like Gaunt whom I suppose might be exhausted after a while, or mere opportunism of would-be predators who try to invade to get the wealth of a kingdom on the cheap as they hoped, only to find themselves checked and repelled and re-evaluating the new regime as a force to be treated with care and respect?

If they are going to prosper at all in England, the peasants mainly just want to be left alone, but the fact is a certain amount of trade is also part of their lives and if that dries up completely, they won't be happy about it--however much they distrust, or outright hate, actual traders they do tend to meet. That's why the mob in London went on a pogrom against the Flemings of course, or anyone who said "eggs and cheese" in accents the mob members present thought might be Flemish. The Flemings had a de facto monopoly on the wool trade and common English people had serious resentments against what they thought of as sharp practices (we'd probably agree with the peasants too if we had to trade on analogous terms I'd think, though surely we wouldn't think we'd just ethnically cleanse them, or anyway hope not). Certainly the better off classes would deem it quite a hardship to do without foreign trade.

But would not the various Continental authorities, even if they find it a fool's errand to send invaders to try to conquer England in toto, at least attempt to close their ports to any English ships, and set upon any English crews that attempt to land, lest they spread the contagion of this grassroots vague egalitarianism?

Then there is the religious angle to consider. I sometimes encounter a sort of Whiggish idea among some British and other writers here (people I tend to respect a lot on many points, I hasten to add) who make much of a long and deep seated English opposition to the pretensions of the Roman Catholic church, sometimes in the context of ISOTs or PODs to pre-Norman invasion times, the Anglo-Saxon era, often combined with the idea that the Celtic Rite of Catholicism was actually another species of the same inherent British antipathy.

Well, on one hand, certainly the British Isles are isolated to a degree, off in their own peripheral world, as seen from Roman perspective, and a certain divergence is only to be expected, then in an age such as the High Middle Ages where the power of the Papacy, and also other Continental powers such as the HRE which in some contexts is allied to the Popes, the various British peoples have relatively little influences in the central courts of such powers and will tend to have their peculiar inputs ignored or overruled. But at the same time, I think if we look at both the successive conversions of first Ireland then Saxon England to Christianity, we find actually quite a lot of convergence of moods and interests too. The Irish rite was divergent largely because of geographic distance and semi-independent development, but the Irish remained in communication with the Continental church, and to a large degree helped shape key aspects of overarching Roman Catholicism as it achieved effective co-hegemony with their secular noble allies.

Certainly there was a lot of grassroots discontent with this and that, and certainly the various dynasties, Saxon and then Norman, had their clashes with the Curia, largely over control of appointments to the Church upper hierarchy. But this was also true to some extent all across the Continent, especially in places rather far from Rome--and a lot of the high level Church/State conflicts that did emerge proved to be essentially tactical quarrelling, with regimes that were on the outs with Rome in one generation switching sides in another as expedient, and of course the Church repeatedly suffered schisms in the matter of which of two (and maybe sometimes more?) persons were the "true" Pope. It was a political game at that level; at the level of grassroots discontents, it was generally resolved with the authority of the Church siding with the authority of secular overlords to repress unrest across the board.

Now England is in one of many such episodes, and we've adopted a POD whereby Richard II is captive, and might come round to becoming a willing and able leader of, a major grassroots rebellion. And many of the issues the rebels are up in arms about are those perennial grassroots discontents with clergy they deem corrupt--for reasons I think most modern people of whatever sectarian background would agree had some solid foundations indeed. If Richard II is going to go on riding this half-broken bronco and retain the allegiance of the mob he and they have sworn some mutual fealty to in the name of a commonwealth of all, he will perforce have to at least rein in the Catholic hierarchy's impulse to protest many a local grassroots overturn of the hierarchal order. We've already seen the peasant armies burn down Cambridge and the Bishop of York mediating a truce quite mindful of the mob's potential to wreck everything, or anyway everything that matters to the established elites of Yorkshire, clerical and secular alike.

"Lollardry" has been alluded to already too, paradoxically perhaps as part of John of Gaunt's own favored leanings, though it has been stressed the radical clergy have not yet quite crossed the line that marks them as heretics, and the only person so labeled and condemned so far is on the rebel side, Ball. In some matters, the mob might actually prove quite orthodox versus the leanings of some of the old regime nobility actually.

But it seems pretty much a foregone conclusion--not because the English are specially some kind of natural "Anglicans" with the King James Bible or some Middle English edition of it and the Book of Common Prayer ditto in their blood somehow along with Caesaropapism, but simply because the mob, all across Europe and throughout the entire Middle Ages and into modern times, is quite often out of step with the Catholic hierarchy on this or that point--that Richard must either flee and seek refuge elsewhere, or give his assent to something or other the Curia, and with them many otherwise rival factions of secular rulers on the mainland, will see as open and shut heresy, and very dangerous in form.

One such item would probably involve clerical marriage. The purported celibacy of proper Catholic clerics was an item of widespread grievance because of course quite a lot of clerics at all levels, including most pointedly to the mobs, the lowest, would violate it, use their privilege to evade obligations to the women (or men I suppose) they abused and fail to provide for the resulting offspring--or vice versa, favor their illicit mistresses and children, which was exactly the kind of diversion from their supposed obligations to the community as a whole that Pope Gregory the Great had meant (along with other reasons) to put an end to when laying down the mandate of universal celibacy on all levels of cleric. English peasant protests quite often were quite cynical about all this, based on extensive bitter experience, and I would think if common villagers felt empowered, the priests and friars they might happen to actually like would be married in pretty short order, and others would be lucky to escape with their lives, and would have to keep running until they had left the kingdom--bearing with them quite lurid accounts of how the English are lapsing beyond mere heresy into outright heathendom. Mind I do suppose that a certain respect for clerical celibacy that is actually sustained, either in honest fact or with the clerics involved being very very discreet and keeping things smooth and respectable outwardly, which I hope would mean perhaps avoiding actual abuse if we discount their breaking the vows as a harm in itself (but sadly modern experience suggests that some abuses that don't antagonize the masses can nevertheless involve severe suffering for some victims who remain silenced and unheeded when they do cry out) and the English church won't abandon the notion that celibacy is a laudable goal to be aimed for by anyone who is very serious in following religious vocation, and ought to be looked for in the higher ranks of the Church especially.

Then there is the matter of translating the Bible itself and other key traditional Catholic texts into English. Actually this is a fairly early juncture for that, though I have the impression the attempt has already been made before the POD. English as such is not yet a very prestigious nor respectable nor much institutionally supported language; at this time the nobility is still learning and speaking Norman French. Though this late, I am pretty sure a version of Middle English is as much their "mother" tongue as the French--their parents would of course insist they learn and master the Norman version of French, perhaps already at this point influenced toward Parisian noble French, quite young and in principle to the exclusion of peasant English--but in reality, a lot of the people caring for noble babies and children will be English speaking servants, and it seems inevitable to me the kids grow up equally proficient in both. And no matter how much disdain there is for the Germanic grammar speaking commoners, it is clearly expedient that every noble however haughtily placed should be able to understand whatever their bondservents are muttering under their breath, and to give them orders in language they can understand--the closer servants will of course have to pick up the prevailing court French they will often be given orders in too, and to answer questions when these answers are demanded in the court language, suitably modified for their humble place.

But in fact the entire lot of all English nobles, whether on the outs with the mob or making uneasy peace with them, will be capable of speaking Middle English, if not proud of it. Someone, in addition to the handful of remaining Anglo-Saxon monastics who in earlier centuries continued the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, will even be writing down stuff in some dialect of Middle English--there is no Chaucer yet, but there is say the Gawain-poet whose name is lost to us, but has already written Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in some northern dialect, and there are other works of Middle English poetry and prose that come down to us OTL, along with recordings of peasant songs and so forth.

Now all of a sudden we have the monarchy placed up on the shoulders of this same mob that either can't speak French at all or knows only something like a "Cockney" version of it, either well in their fashion though far out of step with proper court diction, or poorly. Perforce, business must to some extent be conducted, or anyway repeated for popular consumption, in Middle English. A "proper" court version of it must develop if the new regime is to survive any long time, no matter how much more common English people do learn an acceptable version of French in addition.

An English language Bible being not only written, but one version of it being authorized and blessed by the royal court, and surely I would think by whomever is now Archbishop of Canterbury, seems entirely certain to emerge, again perhaps not in the first few years but I would think long before Richard II would be expected to die a natural death if he lasts that long, or for his successor if he doesn't, within two decades if not much sooner than that.

Let's suppose that the only other divergences from Canon mandates the English church fosters are simply matters of authority to appoint clerics to higher clerical office ranging all the way up to the Archbishop of Canterbury and York, but in fact the English hierarchy believes themselves to be entirely orthodox in their Catholicism, and even deem themselves properly loyal to the Pope (whichever one seems to have the proper legitimacy as they see it at the moment that is).

It's still an ideologically corrosive, indeed explosive, brew for the Continental traditional powers that be, secular and clerical alike. Just these two modest reforms, even without neutering the power of Rome to have some control over national religious hierarchies, that is tolerance of some clerical marriages and the notion that the Scriptures should be made available in local dialect languages, would upset a great many applecarts on the mainland. If anything it is far more threatening to established order there than more extreme heresies such as Albigensianism or the pagans the Teutonic Order went crusading against in recent centuries past, precisely because the disruptive elements slip in under what the mainland authorities would see as a deceptive "veil" of apparent good reason in an otherwise orthodox package.

Obviously this is what happened some centuries later in OTL with the Reformation, but then of course along with some pretty deep revisions in doctrine. I think the people who project modern Anglican dispositions onto all ages of Britons prior to Henry VIII are off base in going that far, and that perhaps there would be far less drive to change most basic Catholic doctrines in this relatively early age. And we can have some doubt that there might actually be an English Bible because English nationalism as we know it today had yet to be defined versus French identity by the Hundred Years War.

But on the other hand we are leaning on running with a Peasant Revolt that does not come a cropper, or anyway not for some years perhaps, and that does favor some elevation of the status of Middle English I would think. To a degree both English and German (and Dutch, and Danish, etc) nationalism does also relate to perpetuation of the Bible, centrally speaking the Gospels, in various vernacular languages that get elevated and consolidated by the choice of exact dialect used by the initial translator--even if nothing like the Hundred Years War ever happens, England will start developing at least some aspects of modern nationalistic mentality just from some English Church canon texts being published in Middle English.

Another difference between this age and the later OTL Reformation era is that the latter happened after Gutenberg and printing in general; in the 14th century any English scriptures or books of common prayer are going to be hand-copied manuscripts and read by relatively few elite people--but these might include now-married village priests after all, addressing the multitude each Sunday and every other Holy Day of Obligation. It seems likely that pretty soon they'd start translating elements of the Mass ritual into local dialect as well, perhaps in line by line repetition, first in Latin then in English--that way, a fair number of the more alert and interested peasant congregants will pick up a smattering of some Latin too even if they are never in a situation where they can learn to read in any language. But I imagine, if we can have a significant degree of social democratization persist and not be crushed and reversed, that literacy will indeed rise, and much more steeply once printing is introduced.

But the mere survival of the kingdom is in some doubt after all. Trade as noted will suffer with foreign traders deterred from making for English ports (at least not unless they come in as part of an invading armada) by the mistreatment of the Flemings which happened both OTL and in thread canon, and the lords, secular and spiritual, on the mainland will either capture and try English crews attempting to make port on the mainland, or threaten them plausibly enough that the ships veer off and if running low on supplies, look rather desperately for somewhere to land and wind up being treated as pirates if not part of an invading navy themselves. All the news these increasingly frightened Continental authorities are getting out of England, from captives and refugees alike, is more and more alarming.

I think there would have to be a Crusade. It might not have the success Continental authorities hope it would, but they are going to try to stamp out all this heathenish devilry pretty quick. It might take them so long to get a proper armada together they waste some effort in penny packet descents shooting as it were from the hip, and between these landings and general civil war in England, this buys time and experience for the new model army that might emerge in England to start forming and acquiring numbers and depth, so that when a properly organized armada comes in, it meets stiff opposition, and ultimately the invaders are killed, captured or send back into the sea to retreat home.

But international trade ties would remain badly disrupted. Perforce the English would have to be autarkic, which is not that severe a hardship for them as it would be in later ages--but they are sidestepping the collective capitalist development of western Europe that happened to be taking root there in this time, and thus probably at best, even if they can secure their autonomy long term, isolate themselves and be bypassed.

I don't see any warrant whatsoever--again unless one is willing perhaps to assert a very alternative path of collective economic self-integration on some non-capitalist basis--to assume that "naturally" they'd develop capitalism internally and become the Workshop of Europe on their own hook, without having previously been reintegrating into those developing transnational institutions along with the rest of Europe.

Now conceivably, English grievances reflect generic ones all across Europe and what they will do is trigger a wave of comparable revolution on the mainland as well, just as the continental authorities would fear. The situation is much more similar to that of the French revolutionaries in the years of the First Republic, and perhaps the mainland response of European orthodox Christendom would be an analog to the massive conservative coalition arrayed against that revolutionary Republic--and I have optimistically suggested possibilities for how the kingdom might manage to survive such a bashing just as the First Republic did, turn overwhelming odds against them into forging new institutions leapfrogging their potentials and react to repeated invasion attempts they learn to throw off with counterinvasions of their own on a reforming countercrusade to raise up continental peasants on a more or less forced, more or less spontaneous, emulation that subjects western Europe to a chain reaction of reformed regimes that ultimately breaks the continental old regime.

But of course the French of the early 19th century, after a couple decades of hegemony, were in the end defeated--here perhaps we can better imagine they'd be checked at some point, and perforce the surviving old regimists of the mainland get hammered into an empire of their own that can hold the frontier, and over time, perhaps many generations, there is a detente of sorts and Europe goes down a radically changed path.

That might or might not involve a resumption of the tendencies to capitalism that might or might not carry England with it.

The thing is, OTL while the First Republic did, in the desperation of their crisis, develop innovations enabling them to first defend themselves and then come back with waves of conquest, this also involved the transformation of what were supposed to be democratic-republican institutions into autocratic ones leading to Napoleon Bonaparte crowning himself an Emperor--and, alongside preservation of certain liberal reforms he did not dare reverse and found useful actually, framed a brand new hierarchy of nobility and privilege quite comparable to the Old Regime in its denial and suppression of mass democracy.

So, if the English can manage to survive this crisis at all on a path that doesn't amount to restoration of the old Norman regime after a brief detour that is only somewhat longer lived than the weeks and months of the crisis of OTL, it seems likeliest that the longer term outcome would be essentially reinventing a somewhat modernized and streamlined improvement perhaps on basically late medieval forms. With the nobility purged and reshuffled, the Catholic hierarchy likewise beaten with a brush and aired out a bit, new men jumped up from the lower ranks take their place alongside old nobles and bishops and abbots who were flexible enough to ride the storm with Richard, and new titles in a new table of ranks simply slot in pretty analogously to the old Norman ones, differently named, but functionally quite similar really. The shakeup and objective advances perhaps put the English on a stronger military basis, perhaps the illusion their king is truly a king for the masses and not just chief Norman oppressor enables the new regime to extract even more service in both taxes and manpower for more efficient forces--and gradually if not all of a sudden, the reforms the peasants rose up for are diluted and whittled down and via shell games neutered one by one and they find themselves once again with purportedly celibate priests maintaining a succession of mistresses and droning down on them at Mass in Latin--if the English holy books are not made to disappear quickly in one swift bonfire, they become more and more sequestered, and their language becomes more archaic until it is just as daunting to later congregations as the Latin ever was.

Yes, perhaps the historic memory that once in their great-great-grandfathers' times, their ancestors did rise up, and put the fear of God in the various bosses all the way up to the King himself, and broke the invaders who sought to refashion their chains again directly and immediately, might inspire a few more to stand up in later eras.

But then again, the reflection that one generation or two later, they were right back behind the plows being extorted by priest, landlord and King alike all jostling one another to take the most, and now have to kowtow to the merchant and then the factory owner too, or be driven from the land to become part of the desperate mobs of London or Manchester facing Royal forces that can beat them down with whiffs of grapeshot or send them in chains to Georgia or Australia....well perhaps the takeaway then is that revolution is in vain?

I don't know. I've gone way past where the author has meticulously taken us thus far, and perhaps there are dreams I have never imagined we might plod our way to down this path.

I like what I have seen so far despite some obvious caveats (I don't see why Tyler and Ball would urge the King in Canterbury to promise free trade for instance, I would think both such a cleric as Ball and the bulk of the peasants marching behind him would be pretty acerbic about merchants in general as well as genocidal toward Flemish wool cartel lords in particular) so I am keen to see where the author thinks it would go.

But whatever good or bad comes of it, I don't think we have a shortcut to realize Britain as it was in say 1928 or 1949 just some decades or centuries earlier. I'd sooner believe they conquer the world as some kind of Christian millenarian communists (or of course, gentle on the whole anarcho-communists limiting their violence to the occasional thrown rock) than that we just accelerate the ages of liberalism as we knew them OTL--and if that happens anyway here, most likely Britain is part of it by changing some names and some hats but basically evolving as OTL, or winds up a sidelined hermit kingdom with ossified peasant socialized poverty as anti-radicals assume any socialist path is doomed to do.

I have always thought the Peasant Revolt with its motto ending "who then was the gentleman?" was pretty inspirational at least in potential, and its OTL ending in royal treachery and murder and general terror both a more than adequate retrospective justification for just about anything the peasants, Tyler, Ball et al might have done that was unfortunate--and a macabre and apparently (for half a thousand years and more anyway) eternal sneer by the victorious elites at the thought of human equality. Picture a boot stamping on a human face, forever, indeed. So, glory becoming tragedy ending in farce and bitterness.

I do have some high hopes, perhaps to be dashed with just as much historic irony as in OTL at some later point, that things an uptimer progressive minded person like myself would call good do come of all this!

However...

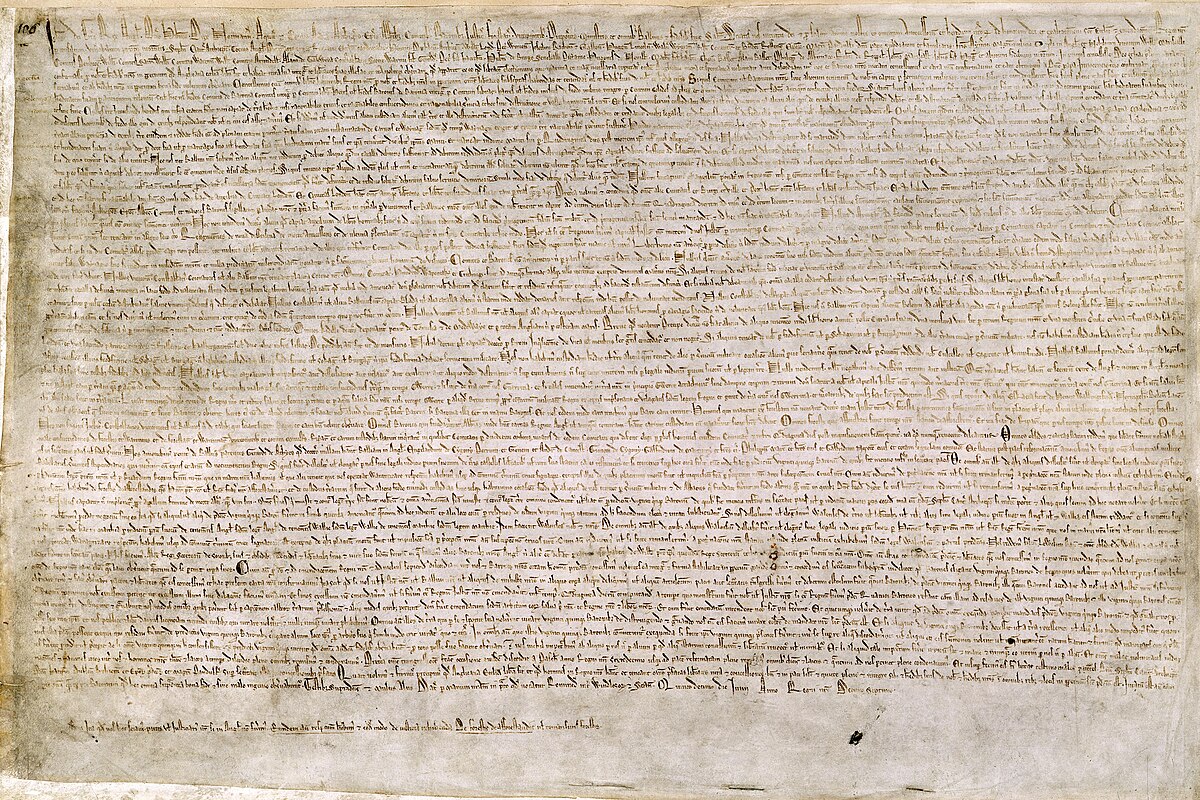

Well, honestly, as a person who finds the radical notions suggested say by Ursula LeGuin in The Dispossessed (which I always hasten to remind people is subtitled by her, "An Ambiguous Utopia,") surpassing the way station of a merely liberal order--actually I suspect a peasant Utopia much more closely resembling the Odonianism of the colonists of the dusty moon Anarres in that novel is about as likely to be the outcome, or sadly more accurately, no more of an insanely ASB long shot, than an early edition of high liberalism, even modified with a healthy respect for the rights of working people--in the context of course of an iron regime of property demanding and commanding ultimate obeisance. Mind it is clear enough to me you mean "over many centuries of evolution" arriving at what is after all pretty much exactly the same place Britain reached by the 20th century.And so we see the peasants' version of the Magna Carta. Whatever it's humble Origins, and however much it influences things and it's time, I can imagine a scenario where people centuries later will use it to try to abolish slavery - if it even begins- and also to call for better salaries and working conditions for laborers.

But in that case--well, a positive glow over an idealization of the pithy spirit of "When Adam Delved and Eve Span, Who Then Was the Gentleman?" is as I say certainly something I for one like, along with such cries as "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" or "As He died to make men holy, let us live to make men free" or of course Lincoln's "government of the people, by the people, for the people."

That's my own idea of glory--to quote a less famous and more ambiguous and ironic song (titled "Marat/Sade" and sung by Judy Collins in the version I know) "...screaming in language that no one understands / of the rights we won with our own bleeding hands/ when we wiped out the bosses and tore down the wall/ of the prison they told us would outlast us all..." That's glory--but the song is about the long term apparent failure--"Marat, we're poor/and the poor stay poor..." which is why the "new generals, our leaders anew" are appropriating the claims of the Revolution, but mocking its content while they "sit and argue, and lie upon their backs..." And why the Marquise de Sade, himself an imprisoned inmate in a Napoleonic lunatic asylum, is putting on this play which ends in the insane cast members mobbing the gentry audience.

At the end of the day, unless the English somehow find a radically different path and one that conventional wisdom dismisses as downright impossible (I don't, but actually achieving anything close to what I'd like to see is clearly hard work and quite likely to fail in the attempt, perhaps not without some long term gains to be sure, though perhaps just as likely or more so, long term damage as well) then England must return to the mainstream path of European development, which means the question of who the Gentlemen were at the dawn of human prehistory is as moot as ever, because we've got new ones now, and their power has a basis. Any success the common people have in uplifting and maintaining their dignity and rights and a place at the tables of power derives from their sacrifices and great risks they run struggling for it, and the ability of their descendants to sustain and maintain their place in the face of new challenges and new opportunities for a few to seize or quietly accumulate power over them as circumstances continue to change. People committed to ideals of modern era humanism including political equality do well to be inspired by the struggles of the past, and even to ignore, or better yet heed and maneuver around, the tragedies of their defeats, but actually it is their integrity, their solidarity, and their prudent actions here and now that really matter, here and now.

They aren't likely to want to be Odonians after all, though honestly I do think the notions of free voluntary contribution to the metabolism of a scientifically understood "social organism" are actually closer to what late High Middle Ages English peasants would want and after thought and deliberation, accept and understand and maybe just perhaps manage to achieve, than the ideals of the liberal ages.

At this stage of human development, the vast majority of the nominal subjects of Richard II, be they the rebels now paradoxically sworn royalist loyalists, reactionary old regimists like Gaunt and the men they either inspire or dragoon into their hard-line aristocratic opposition, or people just trying to keep their heads down and out of range of swung scythes and swords and arrow crossfire, are peasants living in little villages and out-dwellings in the shires who mainly want to be left alone.

If we could have true democracy among these people at this time, what they would demand is massive devolution of government power into their own small scale hands, exercising justice as they see fit, and sadly I fear all too likely to respond to a much lighter aristocratic/royal hand by feuding with each other, at least marginally (mainly, they need to work terribly hard in the hope they might feed themselves adequately over the course of the next few seasons and not look much beyond that)--and of course if they had their way completely, there would be no royal taxes whatsoever, no dues to any gentry, and perhaps not even a very humble and hand to mouth priesthood nor a church--they might want church in the abstract, but would they freely and voluntarily pay to sustain what they expect a church to give them, in material terms?

As for mythic and transcendental nourishment of the soul--again they might actually miss some of what their hitherto traditional churches have been offering them, in sermons, stories and the stained glass window and sculpture illustrations of the medieval take on the Bible and tradition, but they might also find push comes to shove, they can supply enough of that to suit themselves by telling stories and doing some rituals on a volunteer basis. They might or might not then choose to maintain someone as a designated priest, but would they need to accept someone alien to them sent down by some distant bishop, or wait on the approval of one of their own by that same bishop, or miss any training village priests actually got in the old regime that might be lost?

Certainly if we look across the Irish Sea, the early Christian era of Ireland does suggest that such peasants as these English ones might well indeed, on a voluntary basis more or less, sustain a hierarchy of monasteries and look to their clerics for wisdom and judgement.

But meanwhile--could such a peasant confederation of essentially separate villages, far more decentralized than the Heptarchy at its most scattered into tens of thousands of small parochial communities, possibly survive in the late 14th century with the Kingdom of France and the outlying Holy Roman Empire possessions of the Low Countries not to mention the ambitions of kings in places like Denmark all lying just across the Channel and North Sea, and with the still traditionally late feudal kingdom of Scotland right there on the land border (nor have we quite dealt, at this early stage of the author's story, with the situation in Wales yet)? Those likely predatory enemy regimes do command somewhat centralized, somewhat disciplined, relatively expensive armies they can pay for because of ruthless ongoing extortion of their own peasants, just as the dynasties descended from the Norman conquerors in England had in England only yesterday here.

One thing I have lost track of is how much land, and where, on the Continent, was prior to the revolt practically under English rule--certainly any such domains in France would also have the King of France at least claiming suzerainty over them. IIRC a major reason King John in the previous century had to come to terms with his barons at Runnymede resulting in the original iteration of Magna Charta was that his maneuverings brought him to a debacle where he had to sign over all lordship over anything in France back to the French king, in toto, so for a time anyway England had no foothold on the Continent whatsoever.

Now I gather that somehow or other, I forget how and why and where, later kings of England managed to get effective lordship in places like Gascony back into their hands, presumably dynastic marriages were a big part of how it was done, and later OTL of course they surged into France on a massive scale and grabbed control of quite a lot, eventually getting to the point of the later French king surrendering all his domains to the heir of Henry V (whom I suppose is pretty well butterflied away completely already at this point in the ATL narrative).

Meanwhile "now" in the narrative, it is possible these overseas English holdings in southwest France and wherever else they might be have not even yet gotten news of the events of the revolt, but if not they will know about them soon. Just as the English barons were disgruntled and angry and backed their nominal King John into a corner because they had lost their revenues and ties (at least some of them might well have been born and raised in the demesnes now lost to them in Normandy) so many of the lords on the mainland will not take the loss of control of their holdings in England lightly, and will respond to a call to rectify matters by restoring a version of the old regime in England--and might well agree to considerable setbacks in their power and claims in England and even in France to get just a part of their English claims back. And therefore for instance come to terms with the King of France, or perhaps some other adventurer such as some delegate of the Holy Roman Emperor, or some Scandinavian king, to join forces with them to invade by sea.

Can England, even if we were to make little of the further hurdles the Tyler-Ball led movement, and figure Richard plays a most useful role in tying together a new regime fast, hope to defend itself by sea alone?

Well, of course the English lean more heavily on navigation than the average 14th century northern European nation does (maybe not more so per capita than say the Norwegians or even Danes, but of course those two branches of the Danish crown lands have rather low populations versus England; the Flemings, with the proto-Dutch a peripheral backwater to their north, have considerable investment in shipping too). And for that matter as anciently as the reign of Alfred the Great, and with only half of England in his control at that, England did muster a substantial navy.

But in this era, we are still pretty far away from the concepts of modern sea power after all. To begin with modern naval warfare is defined by firepower and the ability of warships to either repel, evade or endure heavy shelling/bombing; in this pre-gunpowder era (well I think it is just starting to emerge in European warfare, but at the very beginnings) a naval battle, such as they were, is either a matter of ramming enemy ships to sink them, or grappling with them so the two ships' crews can fight it out hand to hand.

Also and very importantly, navigation itself is still pretty primitive, and ships generally don't go exactly where their pilots and helmsmen might wish them to go; chance is a huge element and fleets are pretty hard to keep together, tending to be scattered and wind up at various somewhat random destinations.

Alfred's "navy" then, and IIRC Harold of Wessex had one up and running hoping to have some defensive effect, was a matter of coastal patrol at best, and could reasonably be expected at best to give some early warning of an incoming invasion fleet, with good luck anyway, and perhaps to attrit or divert such an invading armada, if in fact the English could maintain enough hulls diverted to such armed defense, which is of course a major drain on the royal exchequer or alternative paths of funding, while removing the hulls from the useful business of trade. (In this era and for some time well into the early modern one, a good warship was largely interchangeable with a decent merchant ship; a navy was largely a militia of merchant hulls and crews carrying warriors instead of revenue cargo, with some more specialist ships such as galleys in the Mediterranean being the warships as such, but in northeast Atlantic waters such vessels were not much favored!)

Richard can't rely on "wooden walls" alone to keep the peace for his landlubber peasant subjects then; the kingdom requires some kind of army, and one numerous enough to stand ready to fight and defeat major landings anywhere the combination of invader plans and the fate of fitful winds might bring them on the English coasts.

This is assuming of course that whatever armed forces Richard can maintain in the name of his restive peasant subjects are not engaged up to their necks in hard fighting of yet more reactionary gangs in various remaining strongholds, say in Wales (where mere reaction in favor of the old Norman style aristocratic regime might merge or clash with revived Welsh proto-nationalism seeking to set up a new Welsh kingdom or possibly some kind of republic, Wales for the Welsh (Cymru I suppose, by this late date, would be the actual name would it not?) Conceivably, if the spirit of the Peasant Revolt has spread organically to Cymru lands as well, a parallel Welsh regime might come to reasonably mutual agreeable terms with a strictly English one, if Richard is prepared to agree to relinquish control over lands some English king or other has more often than not controlled for centuries--but even with a truce in place and an amicable divorce, such a Cambrian regime might find it expedient to ally with Richard's continental-backed foes, and even when it seems relations between London and Cardiff (if that is where a Cambrian court would settle, in this era I suppose it might be in a lot of other places instead) are pretty good and the "Welsh" interest seems to harmonize well with the English one, still some kind of garrison border defense would have to be kept up in place by any prudent English regime--a diversion of strength a king of England who is in this position of having to placate common mobs because the most expedient taxes his ministers could imagine were the trigger of revolt, in particular then, can very ill afford. Far better if Wales falls into line, even if it means special concessions, and its defense is incorporated--but can Richard, ruling for the moment by consensus of a peasant mob, manage to do that when he couldn't even forestall this mass rebellion of English?

Then of course there remains Scotland to the north, for the moment anyway not facing any peasant revolts of its own, though perhaps that could change, which has allied with John of Gaunt once already--and got their clock cleaned to be sure, but sending the Scots back to Scotland is one thing, deterring them from striking again, and again, and again whenever they think it expedient, is something else.

The author has already dropped the hint that the conservative armies have a distinct per capita advantage of relative established discipline and professionalism of a sort, in remarking how they suffered a lower rate of attrition than the Peasant-Royal Loyalist alliance did. In part it was just that the latter had marginally higher numbers, and mainly that they had better luck, that bought the new nominally royal actually rebel commonwealth some further breathing room and time.

Of course presumably, the more battles the ragtag Loyalist, if I can call them that, forces fight, the more their forces will tend to find ways to get their act together tactically and strategically, and eventually they will be overall a match for traditional late medieval forces.

Indeed we might imagine ways they might stumble into surpassing them, if forces raised from more or less voluntary levee en masse peasants will learn and accept appropriate kinds of self-discipline and turn spur of the moment wiles into consistent battle doctrines. Already on the Continent IIRC pikemen have developed in the Low Countries and perhaps elsewhere, like Switzerland maybe by this date, to check the pretensions of mounted knights, and at all stages foot soldiers have never been completely eclipsed.

Meanwhile even the Normans--one might say especially the Normans, with William the Bastard/Conqueror keenly aware of the need to keep his Norman and Flemish barons under as much central control as he could manage--built on or reinvented older English traditions of fairly central, at least in theory, loyalties of royal forces, and reinvented over time a semi-consensual balance of power between monarch and dispersed local power with an eye to realm unity and general domestic peace while standing ready to either repel invaders--or invade in their turn. It is entirely possible this political revolution, if it can consolidate and establish a track record of more military success, might foster both significant social transformation, either streamlining away hereditary nobility completely or anyway anchoring English lordship again to a continuous national regime served by a unified (if somewhat dispersed) army.

But if the peasants are not to suffer the same fate as OTL just a few years later if that, such an army has to lean on the villages themselves agreeing to shoulder the burden, to pay considerable sums of wealth in some form or other to sustain the forces, land and sea, and to allow their own sons (and daughters, there are always a few women sneaking into nominally all-male forces, generally by disguising their sex) to be taken off to be drilled up into soldiers and often never return, either being killed off or winding up settling into life somewhere far away. Meanwhile the crops still have to be grown, peasant industry still has to be performed. Perhaps indeed they will sacrifice far more for a kingdom they see as their own, with its fighters fighting to protect their own peace such as it is, than they were willing to see extorted by haughty overlords. But how much margin do they have before their villages collapse into famine anyway?

And of course the actual composition of the forces that did repel Gaunt and King Robert of Scotland was by no means entirely some New Model Army 14th Century Edition composed entirely of patriotic peasants. No, their leaders, even the most grassroots and unpretentious of the lot, were veterans of the older wars, and in fact we have some Gentlemen of the old school expediently allied to them. Clearly there will be limits to the general consensus and amity of such mixed forces, however successful they might prove to be in repelling invaders and suppressing diehard conservative opposition.

Who now is the Gentleman? Well, King Richard to start with, and however much intelligent peasants might thrill at the idea he is a divinely ordained King of the common people (certainly anyone literate in Latin, or getting ahold of a wildcat English Bible, can draw and expound some inspiration from the Old Testament here, though certainly the Book of Samuel itself contains the warnings of that very prophet that the Children of Israel would regret setting up a king, be he Saul--or David for that matter; it's a bit of a two-edged sword ideologically speaking!) in fact Richard is the child of late Norman legacy nobility, and surely sees himself as much as the first lord among a distinct and superior lordly class as he might be flattered to be told he is also separately the King of the smelly and ignorant and properly submissive commoners.

Then we have other fellows quite as noble as Richard also marching for the moment to what must seem an awkward and dangerous cacophony of different peasant drums--how soon will be, if ever, they reconcile themselves to a less lofty social role, with fewer or in theory no divisions setting them well above the common masses as special men set by God to rule these sweaty and dirty sheep, and to appropriate their hard work in luxury and power as a matter of right?

But the mob can hardly turn on them and hang or otherwise massacre the lot of them just yet, and expect to survive--and since in fact the mob really is composed of shrewd, intelligent people who can see the realities they face, they won't be too careless just yet either and go on stringing their nominal lords along, and perhaps hope for some kind of easy settlement in the sweet bye and bye.

Now suppose England manages to square all these circles and a fairly secure and consensual regime does emerge, with Richard II having the wit and integrity to stay perched on top and his council however eclectic capable of hammering out policy after policy the villagers (and townsfolk, I haven't mentioned them because they are a minority, but they sit at some pretty crucial junctions of power and are definitely players in this game too) will accept and support.

What is England's larger geopolitical situation, aside from the specific obsessions of old regimist conservatives like Gaunt whom I suppose might be exhausted after a while, or mere opportunism of would-be predators who try to invade to get the wealth of a kingdom on the cheap as they hoped, only to find themselves checked and repelled and re-evaluating the new regime as a force to be treated with care and respect?

If they are going to prosper at all in England, the peasants mainly just want to be left alone, but the fact is a certain amount of trade is also part of their lives and if that dries up completely, they won't be happy about it--however much they distrust, or outright hate, actual traders they do tend to meet. That's why the mob in London went on a pogrom against the Flemings of course, or anyone who said "eggs and cheese" in accents the mob members present thought might be Flemish. The Flemings had a de facto monopoly on the wool trade and common English people had serious resentments against what they thought of as sharp practices (we'd probably agree with the peasants too if we had to trade on analogous terms I'd think, though surely we wouldn't think we'd just ethnically cleanse them, or anyway hope not). Certainly the better off classes would deem it quite a hardship to do without foreign trade.

But would not the various Continental authorities, even if they find it a fool's errand to send invaders to try to conquer England in toto, at least attempt to close their ports to any English ships, and set upon any English crews that attempt to land, lest they spread the contagion of this grassroots vague egalitarianism?

Then there is the religious angle to consider. I sometimes encounter a sort of Whiggish idea among some British and other writers here (people I tend to respect a lot on many points, I hasten to add) who make much of a long and deep seated English opposition to the pretensions of the Roman Catholic church, sometimes in the context of ISOTs or PODs to pre-Norman invasion times, the Anglo-Saxon era, often combined with the idea that the Celtic Rite of Catholicism was actually another species of the same inherent British antipathy.

Well, on one hand, certainly the British Isles are isolated to a degree, off in their own peripheral world, as seen from Roman perspective, and a certain divergence is only to be expected, then in an age such as the High Middle Ages where the power of the Papacy, and also other Continental powers such as the HRE which in some contexts is allied to the Popes, the various British peoples have relatively little influences in the central courts of such powers and will tend to have their peculiar inputs ignored or overruled. But at the same time, I think if we look at both the successive conversions of first Ireland then Saxon England to Christianity, we find actually quite a lot of convergence of moods and interests too. The Irish rite was divergent largely because of geographic distance and semi-independent development, but the Irish remained in communication with the Continental church, and to a large degree helped shape key aspects of overarching Roman Catholicism as it achieved effective co-hegemony with their secular noble allies.

Certainly there was a lot of grassroots discontent with this and that, and certainly the various dynasties, Saxon and then Norman, had their clashes with the Curia, largely over control of appointments to the Church upper hierarchy. But this was also true to some extent all across the Continent, especially in places rather far from Rome--and a lot of the high level Church/State conflicts that did emerge proved to be essentially tactical quarrelling, with regimes that were on the outs with Rome in one generation switching sides in another as expedient, and of course the Church repeatedly suffered schisms in the matter of which of two (and maybe sometimes more?) persons were the "true" Pope. It was a political game at that level; at the level of grassroots discontents, it was generally resolved with the authority of the Church siding with the authority of secular overlords to repress unrest across the board.

Now England is in one of many such episodes, and we've adopted a POD whereby Richard II is captive, and might come round to becoming a willing and able leader of, a major grassroots rebellion. And many of the issues the rebels are up in arms about are those perennial grassroots discontents with clergy they deem corrupt--for reasons I think most modern people of whatever sectarian background would agree had some solid foundations indeed. If Richard II is going to go on riding this half-broken bronco and retain the allegiance of the mob he and they have sworn some mutual fealty to in the name of a commonwealth of all, he will perforce have to at least rein in the Catholic hierarchy's impulse to protest many a local grassroots overturn of the hierarchal order. We've already seen the peasant armies burn down Cambridge and the Bishop of York mediating a truce quite mindful of the mob's potential to wreck everything, or anyway everything that matters to the established elites of Yorkshire, clerical and secular alike.

"Lollardry" has been alluded to already too, paradoxically perhaps as part of John of Gaunt's own favored leanings, though it has been stressed the radical clergy have not yet quite crossed the line that marks them as heretics, and the only person so labeled and condemned so far is on the rebel side, Ball. In some matters, the mob might actually prove quite orthodox versus the leanings of some of the old regime nobility actually.

But it seems pretty much a foregone conclusion--not because the English are specially some kind of natural "Anglicans" with the King James Bible or some Middle English edition of it and the Book of Common Prayer ditto in their blood somehow along with Caesaropapism, but simply because the mob, all across Europe and throughout the entire Middle Ages and into modern times, is quite often out of step with the Catholic hierarchy on this or that point--that Richard must either flee and seek refuge elsewhere, or give his assent to something or other the Curia, and with them many otherwise rival factions of secular rulers on the mainland, will see as open and shut heresy, and very dangerous in form.

One such item would probably involve clerical marriage. The purported celibacy of proper Catholic clerics was an item of widespread grievance because of course quite a lot of clerics at all levels, including most pointedly to the mobs, the lowest, would violate it, use their privilege to evade obligations to the women (or men I suppose) they abused and fail to provide for the resulting offspring--or vice versa, favor their illicit mistresses and children, which was exactly the kind of diversion from their supposed obligations to the community as a whole that Pope Gregory the Great had meant (along with other reasons) to put an end to when laying down the mandate of universal celibacy on all levels of cleric. English peasant protests quite often were quite cynical about all this, based on extensive bitter experience, and I would think if common villagers felt empowered, the priests and friars they might happen to actually like would be married in pretty short order, and others would be lucky to escape with their lives, and would have to keep running until they had left the kingdom--bearing with them quite lurid accounts of how the English are lapsing beyond mere heresy into outright heathendom. Mind I do suppose that a certain respect for clerical celibacy that is actually sustained, either in honest fact or with the clerics involved being very very discreet and keeping things smooth and respectable outwardly, which I hope would mean perhaps avoiding actual abuse if we discount their breaking the vows as a harm in itself (but sadly modern experience suggests that some abuses that don't antagonize the masses can nevertheless involve severe suffering for some victims who remain silenced and unheeded when they do cry out) and the English church won't abandon the notion that celibacy is a laudable goal to be aimed for by anyone who is very serious in following religious vocation, and ought to be looked for in the higher ranks of the Church especially.

Then there is the matter of translating the Bible itself and other key traditional Catholic texts into English. Actually this is a fairly early juncture for that, though I have the impression the attempt has already been made before the POD. English as such is not yet a very prestigious nor respectable nor much institutionally supported language; at this time the nobility is still learning and speaking Norman French. Though this late, I am pretty sure a version of Middle English is as much their "mother" tongue as the French--their parents would of course insist they learn and master the Norman version of French, perhaps already at this point influenced toward Parisian noble French, quite young and in principle to the exclusion of peasant English--but in reality, a lot of the people caring for noble babies and children will be English speaking servants, and it seems inevitable to me the kids grow up equally proficient in both. And no matter how much disdain there is for the Germanic grammar speaking commoners, it is clearly expedient that every noble however haughtily placed should be able to understand whatever their bondservents are muttering under their breath, and to give them orders in language they can understand--the closer servants will of course have to pick up the prevailing court French they will often be given orders in too, and to answer questions when these answers are demanded in the court language, suitably modified for their humble place.

But in fact the entire lot of all English nobles, whether on the outs with the mob or making uneasy peace with them, will be capable of speaking Middle English, if not proud of it. Someone, in addition to the handful of remaining Anglo-Saxon monastics who in earlier centuries continued the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, will even be writing down stuff in some dialect of Middle English--there is no Chaucer yet, but there is say the Gawain-poet whose name is lost to us, but has already written Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in some northern dialect, and there are other works of Middle English poetry and prose that come down to us OTL, along with recordings of peasant songs and so forth.

Now all of a sudden we have the monarchy placed up on the shoulders of this same mob that either can't speak French at all or knows only something like a "Cockney" version of it, either well in their fashion though far out of step with proper court diction, or poorly. Perforce, business must to some extent be conducted, or anyway repeated for popular consumption, in Middle English. A "proper" court version of it must develop if the new regime is to survive any long time, no matter how much more common English people do learn an acceptable version of French in addition.

An English language Bible being not only written, but one version of it being authorized and blessed by the royal court, and surely I would think by whomever is now Archbishop of Canterbury, seems entirely certain to emerge, again perhaps not in the first few years but I would think long before Richard II would be expected to die a natural death if he lasts that long, or for his successor if he doesn't, within two decades if not much sooner than that.