Chapter 11 – Wretches Detestable on Land and Sea

January 1383 – March 1383

"I am your captain, follow me!"

– Richard II of England

King Richard was unsatisfied as he sat at the head of the table eating his dinner of spit-roasted pork with warm pandemain bread, scallions and green vegetables. He may be the King of England, sitting at the head of the royal table inside the candle-lit dinner chamber, yet he felt as though he were being held as a hostage in a foreign realm awaiting release upon the payment of a suitable ransom. The royal palace at Eltham was one of the finest royal residences in London, the revolters had left the King’s own residences untouched, but to Richard it may as well be a common dungeon. Wat Tyler’s appointed guards standing like gargoyles outside the Palace may as well be his jailers. The Lord knew that his annointed-on-earth had about as much freedom to roam as did a common prisoner, especially since Bolingbroke had tried to make a run for it. Poor soul.

That detestable Kentish rustic Tyler had held England in his grip for over a year and a half now, since the summer uprisings in 1381. Was God on that commoner’s side? How else could his successes be explained, unless he were an agent of Antichrist, or sent to hasten the End Times. No, he did not appear to be devil incarnate, but he was a menace to the realm all the same. Perhaps the villeins’ demands that summer had been just. As he sat eating, he thought that perhaps the concessions in those initial charters, granting the end of serfdom, had been just. If the rebels had accepted those terms and gone home, order could have been easily restored and the country could be at peace. Instead, England had suffered from the battles, the destruction of great works, and the burnings. A sharp shiver shot up Richard’s spine.

Why had he been spared? Many other great men had not. Sudbury, Hailes, Arundel, Warwick, all long gone along with many others. What had made them spare his life? Did they genuinely respect him? They bowed in his presence and called him “Your majesty” which he liked, assuming they meant it. Did such thoughts hold after this long or were they mere theatrics to keep up the image that having no intention of dethroning God’s annointed, merely wishing to ‘advise’ him – more accurately to use him to give their actions a legal veneer through royal authority.

He was King in name only. His realm was being ruled without him at its healm, it made him feel powerless, it made him angry, it made him feel sick to his royal stomach. When he could, he shared his thoughts with the few people he could trust, such as Bolingbroke or his mother, the Dowager princess of Wales Joan of Kent. William Montagu, formally the Earl of Salisbury, also often listened to him, though he was often away working in Tyler’s army.

Bolingbroke was only alive because he’d used his royal authority to spare the boy. The two remained close friends despite Tyler’s deep mistrust of him as the son and heir of John of Gaunt. But so long as Richard trusted and protected him, he was safe, until he’d made off in the night. Then Richard could not protect him any longer after Bolingbroke, and his fate was now entirely in his own hands. Tyler had decided plainly that this 'traitor' was to be dealt with like all the others, and had attainted him like his father. Only time would tell whether Tyler's men would catch Bolingbroke before he could make it to Scotland. He hand't even told Richard of his plans to escape, so he was just as much in the dark as anyone else. What would Gaunt himself think if his son was caught and killed? Would he blame it on Tyler, or on Richard? He had no idea, except that he would have no say in the matter himself for he had not reached majority, and would not for another five years.

Is that how long it would be? Would he have to sit on his hands and wait five years whilst his country was ripped to shreds from beneath his feet? The thought made fury boil up inside him. When he got the chance to rule, he would RULE. He would be nobody's puppet King, he would rule as God's annointed should. He would be in control of himself and in control of his realm.

Since the revolt began in 1381, much of its success could be explained by the cooperation (willingly or otherwise) between King Richard II and the Revolters led by Wat Tyler. Royal approval allowed the Revolters to seize control of many of the institutions of government including the law courts, Parliament, and the Church. Since the beginning, Tyler and his colleagues had always paid respect to the King and his immediate family, including his mother Joan of Kent [1]. Their quarrel was not with the young King himself, seen universally as God's annointed ruler and as such was sacrosanct, but with his 'evil advisers' who misled him [2].

By 1383, Richard had still not reached the age of majority (21), and thus was advised by a Revolter-controlled "regency council" with Tyler leading. This fact also played into the hands of John of Gaunt and his allies, who could claim quite accurately that Richard was being held a captive.

For his part, Richard was beginning to find the situation he was in frustrating. He had all but allowed Tyler and his men to seize control of England, first out of necessity by agreeing to their initial demands, and then by the fact he had become trapped by the circumstances. He'd witnessed Tyler's army fight at both Brompton Field and Southwark, the latter from the Tower of London. Those events, as well as the burnings had left a firm impression upon the young Richard, not one that entirely aligned with the rebels vision for England. What Richard had learned was that a lack of firm royal authority would lead England into anarchy and brutal violence, an attitude that would shape the actions later in his reign.

Richard felt suffocated by his inability to rule as he believed a King should. In 1383 he turned 16, but events had matured him faster and his worldview was becoming increasingly solid. There were people close to Richard with whom he could confide. People like his mother, Joan of Kent, and Henry Bolingbroke [3], the son and heir of Lancaster himself. Bolingbroke had been spared from immediate death in 1381 by Richard's own intervention. In the eyes of the Revolters, Bolingbroke was as much a symbol of Gaunt as his misrule as his palaces and jewels were, but with the King himself intervening to protect him they could do nothing to him. With Gaunt's heir as Richard's personal prisoner (in name only), Richard had grown close to Bolingbroke and the two had become friends. In that time, Bolingbroke had begun to make moves of his own behind the scenes to break away from his captivity and reunite with his father. It was the fate of Bolingbroke that would trigger tensions between Richard and Wat Tyler, and would alter the nature of the Revolting Wars.

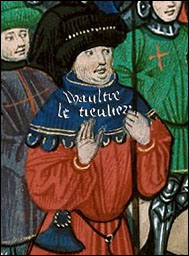

Wat Tyler's stature had grown enormously throughout 1382 and 1383. Through chance, brute force and clever political maneuvering, he had become the second-most powerful man in England, besides King Richard himself. It was he who had guided the commons to the King, it was he who had triumphed by will of God at Brompton Field and at Southwark, and it was he that would rid England of the forces of Gaunt, the whores of Lancaster. His image had grown into a personality cult, with Tyler's name often spoken alongside that of the King. He was seen as "the most noble and memory worthy servant of His Majesty" and a "big brother" [4] to the common English people, who would lead them to the freedom and equality as God had intended when he made Adam and Eve in his image [5].

Despite his apparent successes, all had not gone well. The death of John Ball had shocked Tyler, and had him to take further precautions for his own safety. Upon th opening of the Wonderful Parliament, Tyler had pushed forward the establishment of the

Commons of the Guard of our Lord the King (also known as the

Commons at Arms), a personal bodyguard force to the King and his household, a force which effectively became Tyler's own guards who would follow him and the King at public appearances. The Commons at Arms were posted outside wherever the King was located, and depending on who you asked they were there to guard him or to keep him prisoner.

In March 1383, Henry Bolingbroke had made up his mind to escape London. He had witnessed the events of the past year, and noted that his father and his supposed influence were used to justify the burnings. He had decided that with the escalation of the conflict in England, even Richard may not be able to keep him safe. On the evening of March 14th, he put his plans into effect. He had already established friendly contact with a member of Tyler's Commons at Arms - a Kentishman by the name of Gerald Wright [6]. He quietly slipped away disguised as a groom [7] Wright the 5 shillings he had been promised and was led to the stables where he was united with his horse. From Eltham he departed south towards Hythe where he had made plans prior to his escape to hitch a boat up north and end up in Yorkshire from where he would ride into Scotland and reunite with his father.

Unfortunately for Bolingbroke, his letters had been intercepted. By the time he reached Ashford in Kent on the 18th, he was made aware of men pursuing him. They were certain to be Tyler's men. He went cold. By fleeing he had deprived himself of what little protection he had. If he was caught he was certain to be executed as a traitor. The next morning, Henry get on his horse and galloped like hell towards the Kent downs to the east, reaching the village of Crundale by the evening. His plan now was to reach Hythe via the Downs, hoping to hide amongst the landscape. Here he was, a grandson of King Edward III, forced to play hare and hound with commoners, with stakes that could be deadly.

Footnotes

- [1] This happened in OTL as well, the rebels allowed Joan to return to London after a pilgrimage and provided an escort for the trip.

- [2] An almost constant feature among rebellions in the pre-Enlightenment age. Even during the English Civil war in the 1640s, the stated goal of Parliament initially was to replace King Charles's advisers and steer him towards better rule.

- [3] In OTL, he became King Henry IV after deposing Richard in 1399.

- [4] Not a deliberate reference to 1984, but Tyler did refer to King Richard as a 'brother' in OTL, one of the reasons Richard didn't like him. Here, he learns to pay a bit more subservience to Richard (in name at least), whilst elsewhere his headstrong personality has only grown.

- [5] The revolt was heavily tied in with religious sentiments, with John Ball asking "When Adam delved and Eve snap, who was then the gentleman?" - hence the name of this timeline.

- [6] Another fictional character.

- [7] Groom here refers to the member of the King's household who tends the stables.

Comments?