Chapter 34: The King of Steam and the Count of Coal

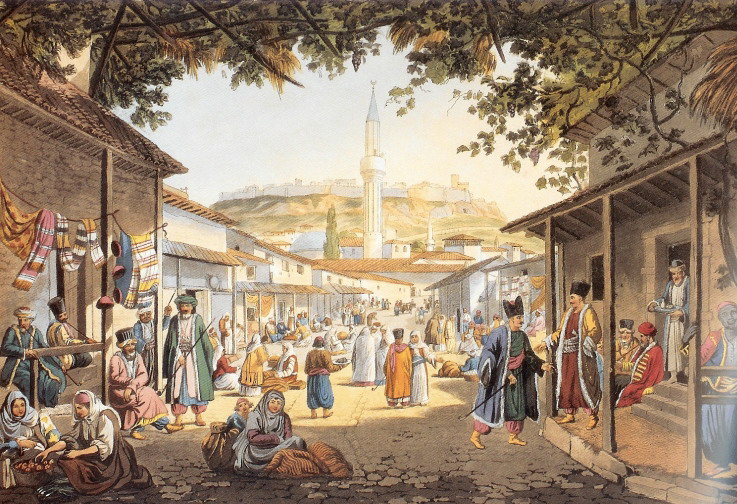

The Bazaar of Athens (Pre-Revolution)

With the political debate settled for the time being, the focus of the assembly turned to the economy. While the islands of Chios, Hydra, Psara, and Spetses among others had gained great wealth under ensign of the Sultan, much of mainland Greece had been a backwater in the Ottoman Empire, relegated to klephts, small farmers, and pastoralists. Some magnates on land did manage to secure great wealth for themselves, but they were generally few and far between, or in many cases they had made their fortunes off the backs of the poor and the downtrodden. Taxation under the Sublime Porte had been equally oppressive, crushing any hope of economic advancement for the regular Greek peasants leaving most to scrape by on a pittance, it was no wonder that Greek men took up banditry to make a living by the tens of thousands.

This dearth of economic wealth in Greece was made worse by the war which saw the complete destruction of Chios and Psara, the sinking of the great merchant fleets of islands, and the devastation of the Greek countryside from Methoni to Missolonghi. Nearly half of the farms, plantations, vineyards, and orchards in the country had been damaged or destroyed, and more than two thirds of the cattle, sheep, and goat flocks of Greek herders had been stolen or killed during the conflict. Efforts by the Greek Government to collect of taxes became an increasingly rare occurrence in war torn Greece as warring bands of Ottoman, Albanian, and Egyptian soldiers pillaged the land with relative impunity from 1821 to 1829. Without any real means of generating an effective income, the Greek Government was forced to take out loans to finance the war effort against the Ottoman Empire.

Over the course of the war, Greece developed a debt exceeding 3,000,000 Pounds Sterling. Nearly 2.8 million Pounds were borrowed from the city of London and the London Greek Committee, another 20,000 Pounds had been loaned by the Russian Tsar Nicolas, with the remainder coming from private banks, investors, and Philhellenes. While some expected nothing in return, others were not as generous and desired a return on their investments at some point within their lifetimes. To that end, Leopold was forced to ask for another loan from the Great Powers upon his ascension to the throne of Greece amounting to 60 million French Francs or 2.5 million British Pounds.

[1] When the first installment of £833,333 arrived in 1831, it was spent in a matter of weeks, with much of it going towards a myriad of issues.

The largest allocation by far was the expenditures on the military, at roughly 15.3 million Phoenixes or just over £550,000 between the army and the navy at the end of the war. Next were the payments on the interest for the many loans provided during and after the war, which amounted to over 7.5 million Phoenixes a year (£270,000). Then were the costs of the government bureaucracy itself, which was estimated at 2 million Phoenixes (£71,700). Finally, the amount of money allocated to the restoration projects around the country, such as clearing roads, rebuilding farms, building schools and hospitals, expanding ports, etc., all of which came in at a cost of around 1.94 million Phoenixes (£69,500). Altogether, the total budget for the Greek Government in 1830, amounted to about 26.74 million Phoenixes, or just below £959,000.

[2]

With the addition of the government’s revenue of 7,101,915 phoenixes (£284,077), the Greek government ran a small surplus amounting to about £158,410. Without the most recent loan, however, it was clear that the Greek Government would be forced to borrow more money in the future to make ends meet and to repair the damage it had suffered during the war. It quickly became evident to all those in attendance that Greece desperately needed economic reforms lest it be destined for poverty and bankruptcy. As it was currently oriented, the Greek economy was highly dependent upon agriculture and the transporting of that agricultural product to prospective buyers. To that end it was determined that a large class of free farmers was needed to strengthen the economy. Greece faced a problem though.

Out of a total of 15 million acres (~60,824 km2) of land in the country, only 4 million acres were presently being worked by farmers or plantation owners. Of the remaining 11 million acres, over 2 million acres of land were deemed to be ill-suited for farming; the soil was too poor or the land too mountainous. As such, only 9 million acres were available for agriculture, here again there was an issue as nearly 5 million acres were under the control of the Eastern Orthodox Church. It was clear that land reform was necessary to boost the economy and expand farming production in Greece.

Relieving the Church of their lands would be no easy task. The Patriarch was a puppet of the Ottoman Sultan for all intents and purposes, and would never agree to ceding the property of his church to a state which effectively ignored him, let alone a state which had just broken away from his master, Sultan Mahmud II. Consulting with his ecclesiastical advisor Theoklitos Farmakidis, Leopold came to the decision that he would declare all the Churches within the Kingdom of Greece to be Autocephalous of the Ecumenical Patriarch in Constantinople. In his place, a Holy Synod of Greek Metropolitan Bishops would be established as the predominant authority in the Church of Greece. Leopold and the Greek Government would serve in an observatory role, but in reality they held little to no power over any of the Church's internal proceedings. While the decision initially proved unpopular with many of people at first, over time their fears were placated as little actually changed within the church, outside of its top leadership. The benefits of this decision were more immediate however.

Seal of the Church of Greece

With the consent of the newly established Church of Greece, the Government of Greece subsequently closed 500 monasteries and churches across Greece for having five or less monks or nuns. The lands upon which the Church had sustained itself for hundreds of years were also seized by the Greek Government and between the two nearly 5 million acres of land had been sold by the church. The move to separate the Church of Greece from the Ecumenical Patriarch also allowed the Greek Government to take custody over the Church’s property in Athens, simplifying the movement of Government assets to the new capital. In return for these generous transfers of property, the Government would agree to pay the Church for its administrative upkeep, the services to the local communities, the construction and maintenance of churches, and the training of the clergy.

With the Church liberated from the puppet Patriarch in Constantinople, the Assembly returned to the issue of land reform. In addition to the former church lands, the Government now owned about 9 million acres. Some of this land, roughly 3.5 million acres had been mortgaged during the war as collateral for the loans, even still the Government had just shy of 6 million acres of land currently sitting vacant and unproductive. The only question remained what to do with it. Clearly, they didn’t want to just give it away, but at over 5.5 million acres it was too much land to sit on for long, especially while their debts continuing to mount. Eventually they reached a solution. To achieve their desired outcome of a stronger land-owning class of farmers, Greek families, with a priority towards veterans and displaced refugees, would be extended a line of credit from the Government amounting to 2,000 phoenixes which would go towards the purchasing of vacant property at auctions across the country.

It was also hoped that by distributing this land evenly among the people, that it could decrease tensions between the disparate factions and communities within Greece. To ensure that the land was distributed fairly, a National Cadastre would be established to survey the land and divide it into separate, but equal plots of land. It wasn’t a perfect solution as in many cases, the wealthiest members of Greek society bought several plots of land at these auctions leaving others with nothing, but generally most Greeks managed to walk away with something. It also took some time to fully implement, but by 1841, most of the land had been sold off and by 1846 it was estimated that the average farm in Greece came in around 20 acres, which was considered large enough for self-sustenance. In addition, a fund was to be established to subsidize smaller farmers purchase new farming equipment. Kapodistrias also championed the promotion of potato farming, implementing crop rotation, and utilizing modern farming tools. To that end he himself took up the plow and created his New Model Farm near Tiryns, just north of Nafplion.

[3]

With the perseverance of King Leopold and Prime Minister Kapodistrias, and the continued investment of money and resources by the Greek Government, their efforts paid off and the Greek agriculture economic sector would begin showing signs of a strong recovery by the end of the year. This development created a surprisingly good problem for the Greeks in the coming months. Products headed for the ports of Piraeus, Patras, Nafplion, Heraklion, and Antirrio, among others soon encountered a growing backlog of traffic. The infrastructure of Greece, which had never been great to begin with, had been purposefully worsened by both the Ottomans and the Greeks during the war to impede the other. Roads had been obstructed with boulders, logs, and barricades, while docks had been torn up or their ports had been littered with rocks and debris hampering ships. The Greeks may have grapes and olives in abundance, but they had no means of transporting them to those in demand of their product. Aside from the traditional solution of paving roads and expanding ports, Leopold and several members in his entourage also suggested a more inspired solution, steam locomotives.

During his 15 years in Britain, Leopold had been keenly aware of the latest industrial innovations, but the most intriguing of all was the locomotive. The Greeks were no strangers to steam technology having benefited greatly during the war from the four steamships of Captain Hastings and Lord Cochrane. The possibilities of these modern marvels of engineering captivated the King’s audience who were dazzled at the prospects of a metal carriage pulling people and products across the rugged landscape of Greece with ease and efficiency. Intrigued by the King’s auspices, the Assembly began reviewing plans for possible develop of rail lines running across the entirety of Greece. Very quickly they realized this project would unfortunately need to be delayed for some time due to two important issues, money and coal.

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway, circa 1829

Such an undertaking would understandably be outrageously expensive, even the much more limited plan for a rail line connecting Athens to Piraeus would cost a fortune, a fortune they at present didn’t have. The other issue, coal, was a simpler problem to solve. Greece did in fact possess proven coal reserves on the island of Euboea near the port of Aliveri making it an ideal place for a mine to be opened. In addition, Kapodistrias finally managed to convince the assembly of his long running desire to open an iron ore mine near Dirfys to the north of Aliveri. With the iron and the coal, Kapodistrias proposed the creation of a smelting facility near Chalcis to produce the necessary materials for the construction of railways, locomotives, and steamships. While it would take time to generate the necessary funding and equipment for these enterprises, it was the hope of the Assembly, that mining would begin in late 1832, early 1833 at the latest at both Aliveri and Dirfys, while and the iron smelting at Chalcis would begin no later than 1835. Until then, the Greeks would have to make do with their available resources to mend the infrastructure as best they could.

There were other more pressing concerns, however, as the currency of Greece, the Phoenix was also in desperate need of aid. Originally introduced in 1827 by Ioannis Kapodistrias, the Phoenix was meant to replace the unstable and quickly devaluing Ottoman Piastre. While it was successful initially, it soon ran into problems, namely it lacked the material; copper, silver, and gold, necessary to mint additional coins. As such just under 21,000 Phoenixes had been minted in the nearly four years it had been in existence. Ultimately, foreign currencies continued to circulate throughout the Greek economy in abundance. To deal with the problems surrounding the Phoenix, its value was first fixed at 0.895 French Francs. As precious metals were a rarity in Greece, paper bank notes were distributed to make up the shortfalls in coinage, while more copper and silver was mined and imported. Though the paper money proved unpopular at first, they gradually gained acceptance among the Greek people.

The National Bank of Greece was also in need of reform to aid in the management of the Phoenix. Also established in 1827 by Kapodistrias, the National Bank of Greece was originally envisioned as a government run institution that would serve the role of a central bank for Greece and it would guarantee the security of its investors’ deposits. Suffice to say, it didn’t work. As was the case for much of the war, money was a constant need for the Greek Government with the finances of the state perpetually floating on the edge of bankruptcy. To avoid default, the Government began withdrawing the deposits from the private investors in the bank to continue funding the war effort. As could be expected, the reputation of the bank plummeted and the steady stream of deposits soon ground to a precipitous halt.

To rectify this issue, Leopold and the Greek Government agreed to privatize the bank while retaining significant influence over its activities through regulations. The Government also nominated the Epirote banker and former Finance Minister, Georgios Stavros to serve as the first Governor of the Bank.

[4] The National Bank of Greece was given the sole right to issue bank notes and the bank was permitted to sell shares to investors both foreign and domestic alongside several other services it provided like insurance and asset management. As a sign of good faith, the Government also agreed to make an investment of 1 Million Phoenix in the bank, purchasing 1000 shares in the bank, King Leopold purchased 100 shares, Kapodistrias bought another 100, and various ministers of the Greek government invested in the bank as well.

Next Time: Valor and Great Matters

[1] The French Franc has a value of about 24 to 1 when compared to the British Pound, the Greek Phoenix ITTL is roughly equivalent to the French Franc at one phoenix to roughly 0.9 Francs. For the sake of simplicity, I’m going to use the value in Pounds Sterling when dealing with loans and foreign financial transactions as that’s what I’ve used thus far in the timeline, but when it comes to Greece’s internal economy, I’ll probably stick to Phoenixes (PHX).

[2] The French Franc has a value of about 24/25 to 1 when compared to the British Pound, the Greek Phoenix ITTL is roughly equivalent to the French Franc at one phoenix to roughly 0.9 Francs, making one Pound equal to about 27.9 Greek Phoenixes. For the sake of simplicity, I’m going to use the value in Pounds Sterling when dealing with loans and foreign financial transactions as that’s what I’ve used thus far in the timeline, but when it comes to Greece’s internal economy, I’ll probably stick to Phoenixes (PHX).

[3] Kapodistrias’ Model Farm was more like a school rather than an actual farm. It was intended to be a place where farmers could be informed of the latest innovations in agricultural technology and practices. Unfortunately, Kapodistrias’ death and the poor state of the Greek economy at the time forced it to close.

[4] Georgios Stavros was the OTL governor of the National Bank of Greece during its first run from 1828 to 1831 and its second run from 1841 until his death in 1869. Before the war for independence he worked as a banker in Vienna where he learned his trade and became quite wealthy. He later became a supporter of the Filiki Eteria and met with Ioannis Kapodistrias while in Russia. During the war, he sent supplies to the Greeks before traveling to Greece in 1824 where he served as the Finance Minister under Georgios Kountouriotis and later worked with the Swiss banker Jean-Gabriel Eynard to build the National Bank of Greece in 1828 and again in 1841. With the better management of the loans, the continued support of Kapodistrias, and the earlier reaction to its problem, the bank is saved as opposed to being abolished in 1831.