Chapter 43: Hellas Rising

King Leopold Enters Athens

The 1830’s would prove to be a productive decade for the Kingdom of Greece, full of great achievements, great advancements, and great milestones. Under the firm hand of King Leopold and the brilliant leadership of Prime Minister Ioannis Kapodistrias, Greece began to steadily rebuild after nine terrible years of war. The ingenuity of the Greek people was on full display as they began to thrive once more, the economy of Greece rebounded at a steady pace, and the country was in relative peace. Everywhere from Missolonghi to Heraklion saw signs of great progress, but nowhere was this burgeoning prosperity more noticeable than in the ancient city of Athens.

Established as the official capital of the Kingdom of Greece in 1831, Athens had been relegated to a relative backwater under the Ottoman Empire who disregarded the ancient city and its illustrious past. Before the revolution, Athens had been a small city of around 11,000 people situated at the foot of the mighty Acropolis. With its narrow streets riddled with ancient ruins and much of the land owned by the clergy, it had been left to its own devices by the Sublime Porte who invested little in the city or the surrounding region. With the coming of independence, however, Athens began to blossom into the great city it would become once more.

During the war, Athens would be the scene of one of the great early victories by the Greeks over their Ottoman oppressors in 1822 with the surrender of the Acropolis and the Turkish garrison after a long and grueling siege. With its freedom achieved, Athens would become a bastion of Greek liberty in Southern Rumelia that would remain steadfast against Ottoman incursions into the South. Following the war, through the process of land reform and autocephaly, the clergy were made to sell their land to the Greek State leading to its development and cultivation by the people and the Government began the long and grueling endeavor of moving their agencies, institutions, and ministries from the old capital of Nafplion to Athens over the course of several long years. Displaced refugees with nowhere to return to and rural Greeks from the countryside seeking work settled in Athens by the thousands, boosting the population of the city from just below 8,000 in 1830 to over 15,000 in 1834. Still, more was needed to update the city from a quaint medieval town into a modern capital city.

To that end, Kapodistrias called upon the Greek Architect Stamatios Kleanthis and his Prussian partner Eduard Schaubert to survey and design a new urban plan for Athens.

[1] Making efforts to respect the extensive heritage of the site, Kleanthis and Schaubert painstakingly recorded every ancient ruin, every Byzantine structure, and every contemporary building of the city. The proposal that they landed upon was a neoclassical city with expansive vistas which perfectly portrayed the ancient and medieval wonders of the city in an elegant light while providing the necessities for a modern metropolis. The site would encompass the Northern half of the old city with the New City expanding to the North, East, and West of the Acropolis, while the Southern half of the Old City would be left vacant to preserve its relics and ruins for future archaeological purposes. New buildings were constructed to accommodate the Legislature and the Judiciary, while a relatively grand palace was built to house the King, his family, and his court on the Northern edge of the city. Barracks for the royal guard and gendarmeries were located near the palace, while an expansive market would be placed in the center of the city. The streets were to be widened to allow heavy foot traffic through the city, while gardens and parks were planted across the town to complement the already beautiful panorama of Athens.

Unfortunately, Kleanthis’ and Schaubert’s plan called for the demolition of numerous buildings to clear the necessary space for the three main avenues and the new structures laid out in their proposal. Understandably, this met with intense resistance by the people of Athens themselves as many were faced with destitution following the Government's failure to fully reimburse or adequately move the affected populace. Work was quickly halted due to a series of protests and demonstrations all across the city and while the unrest would eventually be quelled by the local authorities, the point had been made. Another problem which immediately emerged was financing. While the Government would receive the second installment of the French loan in 1832 and the third installment in 1833, the Greek Government simply had too many other expenditures to fully meet Kleanthis’ and Schaubert’s proposals. Without adequate funding the pair were forced to cut back on the more elaborate and grandiose embellishments of their plan for the time being.

After some slight modifications to their plans, a second revised city plan was presented to Kapodistrias and Leopold which was summarily approved. The setting of the royal palace was also relocated from the North to a defile running along the Eastern edge of the city between the Acropolis and Mount Lycabettus and the gardens were sheared down extensively to help cut down on costs. The palace itself was similarly curtailed from the massive abode it was originally envisioned to a more modest venue, although it was still quite impressive compared to the humble houses of the Athenians. The existing roads were to be widened and repaired, rather than replacing them entirely with new avenues. While some continued Athenians remained displeased, the plan went ahead in 1833.

Kleanthis’ and Schaubert’s revised plan for Athens

Kleanthis and Schaubert would be tasked with their most delicate project three years later in 1836, when the pair along with the Danish architect Hans Christian Hansen and the Scottish archaeologist Ludwig Ross, partially restored the Temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis.

[2] As with everything they had done thus far, Kleanthis and Schaubert took great care to protect the ancient temple from further degradation. Other architects and engineers like Hans Christian Hansen, his brother Baron Theophil Edvard von Hansen, and the Greek architect Panagis Kalkos would be responsible for the design and construction of other important structures around the capital such as the Athenian Mint, the University of Athens, the National Observatory, and the Parliament building along with many others. In addition to their work in Athens, Kleanthis, Schaubert, and several other architects were also commissioned to modernize the port of Piraeus and the coastal town of Eretria near Aliveri during this time in preparation for the looming industrialization of the region.

In March 1832, public and private investors established the Aliveri Coal Company (EAK), a privately-owned coal mining entity headquartered in the town of Aliveri. Two months later in May, representatives of the Greek Government together with private interests established the Dirfys Iron Company (DES) and tasked it with conducting iron mining operations in the area around Dirfys. In June 1832, the EAK signed a contract with the Greek Government permitting the EAK to conduct mining operations near Aliveri, while the DES was granted a similar permit to mine the iron deposits near Dirfys later that year in September. With the legal intricacies settled, the EAK and the DES were provided with interest free loans from the Greek Government allowing the companies to begin hiring workers and purchasing equipment and by the end of May 1833 both mines were fully operational. Problems quickly began to arise for both companies however.

The coal was overwhelmingly lignite, rather than the more lucrative anthracite coal, making its profitability much lower than anticipated. Because of this, any plans to trade the coal overseas were immediately dashed and were instead refocused towards domestic use. Production of the coal was also disappointing at roughly 11,000 tons in its first full year due to problems with breaking equipment and labor shortages among other things. The iron ore production was worse at roughly 8,000 tons in the first 12 months the Dirfys mine was open, although this shortfall was made up somewhat with another 2,000 tons of nickel in that same time. Over time though these production totals would gradually increase as deficiencies in the mining process were worked out of their systems and more workers were brought in to mine. As a result, the coal mine at Aliveri would reach a per annum total of 23,000 tons in 1840, while the mine at Dirfys would produce 19,000 tons of iron ore and 6,000 tons of nickel per annum in that same time.

[3] Nearly 1,300 Greeks would be directly employed as miners, engineers, administrators, or managers by the two mining companies while another 500 people would be employed in service vocations supporting the miners as doctors, nurses, entertainers, cooks, etc.

Other mines and quarries would soon begin appearing across Greece in the following years as the success of the Euboean mines became evident. The ancient silver mines at Laurium to the southeast of Athens were reopened in 1839 after being closed for nearly 1,200 years and the marble quarry on the island of Paros was reopened by the architect Stamatios Kleanthis in 1838. Uses for these minerals was usually predetermined well before they left the ground, with the nickel and silver primarily being allocated for the minting of the Greek currency, the Phoenix, while the marble among other things was used extensively in the construction of various monuments and palaces across the country. Some of the coal would go towards residential and commercial heating, but a significant portion was directed towards the new smelting facilities at Chalcis along with the iron ore following the completion of the facility in November 1836, where it was summarily worked into usable products like wrought and cast iron. While most of the iron wares were used on more mundane commodities like farm plows, some of the higher quality cast iron was forged into rail tracks for locomotives.

In 1835 the Athens Railway Company (ESA) was established by the Greek government and private investors, with one of the largest investors being King Leopold himself. The ESA was charged with constructing, running, and performing general maintenance on the railways throughout the Nomos of Attica-Boeotia, although in truth its scope was focused primarily on Athens and its immediate environs. The Greek Government had pushed ahead with efforts to construct their own railway running from Athens to Piraeus in an effort to jumpstart development of the capital region and spur economic growth. While it was technically a private entity run by an independent Governing Board, King Leopold was officially named as the Company’s Honorary President as he was the single largest shareholder in the company and had been instrumental in pushing for the development of railways in Greece.

The Greek Government also supervised the ESA’s initiatives with constant oversight and relatively fair, but firm regulations. Additionally, the State provided generous loans to the company and provided military engineers to help survey an optimal route from Athens to Piraeus. With the ESA organized, the Greek Government pushed ahead with efforts to begin construction of the Athens-Piraeus Railway. A permit was agreed to with the ESA allowing them the right to begin constructing the railway once the appropriate money and resources had been gathered. Like all good plans though, it would take until the end of October 1839 before the first line of track would be laid and the first spike hammered into place, but upon its completion in 1847 it would show immediate dividends.

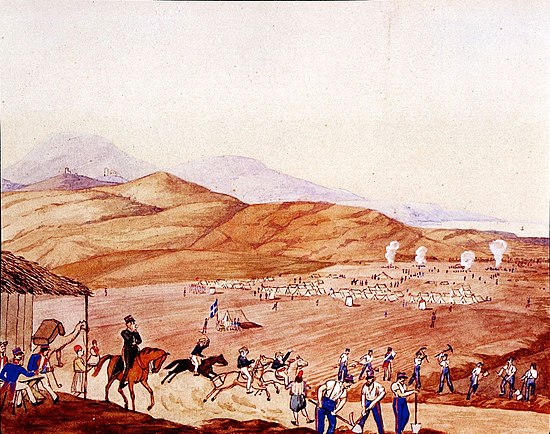

Construction of the Athens-Piraeus Railway

Other lucrative initiatives came at sea with the founding of the Hellenic Steamship Company (EEA) in 1837 by former British Philhellene turned entrepreneurial steamship captain Frank Abney Hastings. Faced with little prospects at home in Britain, Captain Hastings chose to remain in Greece after the war’s end. His career in the Hellenic Navy would unfortunately be ended prematurely by a freak training accident forcing him to retire from active duty. For the next few years, Hastings spent his time as a naval advisor to King Leopold and the Greek Government in Athens and as an instructor at the Hellenic Naval Academy at Piraeus. He would not stay retired long, however, as the call of the sea spurred him to return to the water once again. Investing the entirety of his fortune, Captain Hastings would establish a private steamship company, the EEA, with the approval of King Leopold, Prime Minister Kapodistrias and the Greek Government in 1837. Though it started small at first, Captain Hasting’s company would quickly begin to grow as steamships baring the EEA's colors could be seen operating across the Aegean, Ionian, Adriatic, and Eastern Mediterranean Seas making him an incredibly wealthy man.

Captain Hastings wasn’t the only man to earn a great fortune during the middling years of the 19th century. Various land barons and plantation owners became incredibly wealthy selling Greek cotton, olives, grapes, oils, and wines to a European market in great demand of such products. A small, but relatively competitive textile industry emerged across the countryside, while sponge fishing became an incredibly profitable business for many of the islands. Greek ships once again dominated the waves of the Eastern Mediterranean with Greek merchants found far and wide. Greece also became an increasingly popular venue for young noblemen making their grand tours of Europe, with the ancient ruins and magnificent vistas making for an excellent travel experience. Very soon an entire industry began to emerge in Greece, devoted to the service and support of theses tourists. Because of all these initiatives, the Greek economy made great strides by the end of the 1830’s with the Greek Government achieving its first balanced budget in 1838. The 1830’s were not entirely without their trials, however, as they had their fair share of frustration and disappointments. Nowhere was this more evident than in their dealings with the Ottoman Empire.

Fearing the loss of his Greek subjects to the nascent Kingdom of Greece and citing reports of Greek support for the rebel Albanians and Bosnians, Sultan Mahmud II imposed heavy sanctions upon all trade with the nascent Kingdom of Greece.

[5] Ships flying the Greek ensign were barred from Ottoman ports, Greek merchants were subject to terrible tariffs which threatened to bankrupt them, and immigration to the Kingdom of Greece was strictly prohibited. As trade remained the lifeblood of the Greek economy, this matter was extremely important to Leopold and the Greek Government. The matter was made worse by the flight of nearly three thousand Albanians along with 22 Rebel Beys to Greece in 1834. Faced with calls by the Ottoman envoy to hand over the rebel beys or risk a further deterioration of relations, Leopold was put in a terrible bind.

The kinship shared between the Albanians and Greeks, along with the matter of Greek pride demanded Leopold protect the Albanian refugees against the malice of the Porte, no matter the cost and yet Leopold recognized the heavy cost Greece would likely bare should worst come to worst and war be declared. Unwilling to press the issue more than was necessary as some of his more boisterous advisors desired, King Leopold sought to make amends with the Sublime Porte and began seeking a compromise. Impressed by the tact and diplomatic acumen of King Leopold, Sultan Mahmud relented and the Porte finally came to an agreement with the Greek Government.

The sanctions against Greek merchants would be eased and the Albanian refugees would be permitted to remain in Greece if they so choose, provided the Beys be confined to Crete under careful watch of the Greek government. However, the Greek Government was forced to curtail any efforts by its citizens to propagate seditious activities in the Ottoman Empire. This last term was not received well by the Greek people who loudly proclaimed their support for their Illyrian brothers and saw the cowardly retreat of the Greek Government as a betrayal. Despite this angst, the matter would eventually pass following the birth of the King’s first son later that year, the continued improvement of the economy, and the completion of the 1836 census.

While there had been prior censuses across Greece, their numbers were plagued with inconsistencies and inaccuracies that marred their results. They also lacked extensive information regarding the distribution of the people across the Nomoi making it impossible to fairly allocate legislators to the provinces. The 1835-1836 Census was different however as it had standardized its methods and procedures, making the results more accurate than its predecessors. On the 16th of August 1836 the results of the Government’s official census for the year 1836 returned a total population of 990,825 people.

[6] Given the population at the time of its completion it was believed that the Greek population would cross one million people in the coming months as the 1837 census would later confirm when it returned with a result of 1,011,293. More importantly the 1836 Census finally revealed the population for each Nomos of the country:

1. Nomos of Argolis-Corinthia: 62,116 people

2. Nomos of Arcadia: 124,937 people

3. Nomos of Laconia: 67,614 people

4. Nomos of Messenia: 64,319 people

5. Nomos of Achaea: 87,206 people

6. Nomos of Attica-Boeotia: 86,366 people

7. Nomos of Phthiotis-Phocis: 62,317 people

8. Nomos of Euboea: 43,855 people

9. Nomos of Aetolia-Acarnania: 60,348 people

10. Nomos of Arta: 39,954 people

11. Nomos of the Archipelago: 98,252 people

12. Nomos of Chios-Samos: 50,424 people

13. Nomos of Chania: 61,055 people

14. Nomos of Heraklion: 82,062 people

With the Census complete, the economy continuing to grow, and the country displaying signs of relative stability the Government's justifications for delaying the elections no longer held any weight and the impetus for elections began to grow exponentially. Over the coming days, Constitutionalists and Liberals called on the King and the Government to hold elections as was their responsibility under the law and demonstrations soon began in Athens. While, some within the King's inner circle wished to continue with the status quo as it had contributed greatly to the present prosperity of Greece, most supported elections. Even Prime Minister Kapodistrias believed that the people were ready to take their destiny into their own hands and so after a month of debate and deliberation, King Leopold announced that elections would be held in one years’ time on the 10th of September 1837.

Next Time: The First Election

[1] Kleanthis and Schaubert were responsible for the redesign of Athens following the war in OTL. Initially hired by Ioannis Kapodistrias in 1831, the pair would work for King Otto to modernize Athens and Piraeus before Kleanthis retired from his work after disagreements with the Greek Government and specifically Leo von Klenze the Bavarian court architect King Ludwig had sent with Otto. With the survival of Kapodistrias I see no reason why they wouldn’t do the same in TTL and possibly do even more than OTL.

[2] During the Venetian Siege of Athens in 1687, the Ottomans demolished the Temple for its materials in an effort to reinforce their defenses on the Acropolis. This same siege also resulted in the destruction of the Parthenon and the Propylaea, both of which had been used as powder magazines. The buildings on the acropolis would remain in this sorry state for nearly 150 years before the Greeks finally started to preserve and restore the site.

[3] The first serious attempt to mine coal at Aliveri wouldn’t take place until 1873 and it would only reach an annual production of 23,000 tons in 1920. It would eventually reach its peak production of 750,000 tons per year in 1951 so it is definitely possible to have high coal production at the Aliveri coal mine, but in its early days it will be relatively low especially without more modern mining equipment.

[4] Just for reference, the OTL Athens-Piraeus Railway began construction in 1857 and wouldn’t be finished until 1869. Without the political instability that was prevalent throughout all of King Otto’s reign, having a relatively improved economy, and having a driving force behind the effort Greece is able to finish the railway much earlier than OTL.

[5] While the Greeks had lost their status as the preeminent Dhimmi of the Ottoman Empire, they still remained an influential and wealthy populace who provided numerous economic and societal benefits to the Empire. As such, there was a legitimate concern that Greeks would immigrate to Greece and so the Porte acted to prevent this both in OTL and ITTL.

[6] For those of you who would like to know how I got to this number, I used the 1836 Greek census which reported 751,077 people as a base. From there I added 143,117 people from Crete, 50,424 people from the islands of Chios, Samos, Psara, Icaria, and the Fournoi Korseon. The population for Phthiotis-Phocis was increased by 4,500 people for the towns of Domokos, Almyros, Farsala, Leontarion, and their environs. 30,526 people were added for the Nomos of Arta, which includes Arta, Preveza, Louros and the surrounding area, the remaining 9,428 people from the Nomos of Arta were in the OTL Greece as part of Evrytania which was originally included in the OTL Nomos of Aetolia-Acarnania following independence. 4,500 people were added to the Nomos of Aetolia-Acarnania to reflect the successful escape of the Missolonghi population during their famous sortie, and about 3,500 people were added to Attica-Boeotia to reflect the lack of warfare in the region since Dramali’s invasion in 1822. Lastly, I included the Saronic islands in the Nomos of Attica Boeotia, whereas they were a part of Argolis Corinthia in OTL.