You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Pride Goes Before a Fall: A Revolutionary Greece Timeline

- Thread starter Earl Marshal

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan LeagueIt should be ready later today, I'm making the last edits now.Gotta ask when will the next update be?

Chapter 79: The Price for Peace

Chapter 79: The Price for Peace

Eptanisa joins Hellas

The start of the Great Eurasian War was met with great concern, but also great optimism by many within the Kingdom of Greece who saw this conflict as their best opportunity to liberate their kinsmen still under the Turkish yoke. This opinion was shared by many members of the Greek Government, especially those of the ruling Nationalist Party who openly called for war with the Ottoman Empire to liberate their countrymen and reclaim traditionally Greek lands from foreign oppression. Many Greeks also considered it their solemn duty to aid the Russians in their battle against the Turks, as Russia was their longtime friend and ally, while the Ottomans were their mortal enemy and ancient oppressor. However, Russia’s rather poor performance in the opening weeks of the war would quiet these calls for war within Athens, as many were unwilling to commit themselves to what appeared to be a losing effort.

Moreover, war with the Ottomans would have more dire consequences for Greece this time than a simple fight against the Turks, as Great Britain was formally allied with the Sublime Porte in its current struggle against Russia. Like Russia, Great Britain had been a stalwart friend and ally of Greece since 1827 and had become the country’s largest trade partner, consuming nearly half of all Greek exports by 1853. More than that though, Britain was the closest to Greece politically, as the Greek Constitution was heavily influenced by British liberalism, constitutional monarchism, and the rule of law.

Many prominent Britons, such as Lord George Byron, Lord Thomas Gordon, Lord Thomas Cochrane, and Lord Frank Abney Hastings had traveled to Greece during the Revolution to aid them in their struggle for independence, while others provided significant material and financial support from abroad. Lastly, Britain, alongside France and Russia, had intervened on behalf of the Greeks during the War of Independence, helping them win their independence in 1830. Beyond these feelings of fraternity and gratitude however, there was the existential threat that a hostile Britain would pose to Greece.

In terms of sheer numbers, the British Royal Navy vastly outmatched the Hellenic Royal Navy, outnumbering it and outgunning it in every regard, a fact which utterly terrified lawmakers in Athens. In the event of war between them, control of the sea would be lost to Britain almost immediately, which for a seafaring country such as Greece, would be a death sentence. With control of the seas lost, the mainland would be at risk and Athens would be within striking distance of an Anglo-Ottoman assault.[1] The Greek capital would almost certainly be occupied, their ports would be blockaded, their economy would be ruined, and their people would be oppressed. Nevertheless, a person in the throes of passion is rarely rationale, and with the war swing in favor of the Russians in late Summer - both in the Balkans and Caucasus, the Greeks began increasing their calls for war once more.

Tensions would be heightened in June, 1854 when nearly 40,000 Greeks rose in armed revolt across the Balkans demanding their independence from the Ottoman Empire and Enosis (Union) with the Kingdom of Greece. Distracted by the fighting along the Danube and in Eastern Anatolia, the Sublime Porte had few soldiers in place to police their Balkan territories, enabling the rebels to make rapid gains in the first few days. By the end of July, nearly all of Thessaly south of Larissa had been secured by the Greek revolutionaries, while large parts of Epirus from Paramythia and Tzoumerka to Himara and Argyrokastro had been taken by the rebels, including the provincial capital of Ioannina. The Greeks had less success in Macedonia and Thrace, only securing a few remote municipalities and communes such as Kastoria, Kozani, Xanthi, and Maroneia.

Faced with this great success, even the so-called moderate members of the Vouli began calling for armed intervention in the Ottoman Empire to aid their kinsmen. The matter was not helped by the Ottoman government who promptly dispatched whatever men and soldiers they could spare to contain the revolt, resulting in the brutal suppression of several Greek communities in Macedonia and Thrace. By July 1854, Prime Minister Constantine Kanaris was forced to act, officially mobilizing the Hellenic Military for war.

Greek Prime Minister Constantine Kanaris circa 1860

The mobilization of the Greek Military would not go unnoticed, however, as the British Government quickly learned of this development through their agents in Greece While the Greeks would pose little threat to the combined might of the British and Ottoman militaries, they would still be an unnecessary nuisance for them to deal with, especially with the war against Russia going worse than expected. On paper, the Hellenic Navy was rather small at only 47, mostly outdated ships. However, it featured a growing core of modern steam powered warships including a pair of brand-new Screw Frigates (VP Hydra and VP Spetsai), and four new screw corvettes (VP Miaoulis, VP Kanaris, VP Tombazis, and VP Ástinx (Hastings)).[2]

The Hellenic Navy could also be supplemented by hundreds of civilian vessels, ranging from small feluccas and xebecs armed only with muskets and swivel guns to larger brigs and sloops equipped with more powerful carronades and 24 pounders. However, the real potency of the Greek Navy lay in its sailors and officers who in all the world, were second only to the British in terms of skill and ability. Based on this, the Hellenic Navy and its auxiliaries would likely be great challenge to the Anglo-Ottoman Alliance, striking at their long and rather vulnerable supply lines throughout the Aegean from their numerous ports and coves with relative impunity.

The Hellenic Army was no slouch either. While it boasted a rather small standing army at only 18,000 men in peacetime - comparable to the initial British Expeditionary Army in 1854, it could quickly rise to 44,000 soldiers once its reservists were called to active service. An additional 34,000 men of the Ethnofylaki (the Hellenic National Guard) could be called up in a moment’s notice as well, boosting the total number of trained men to nearly 80,000 in theory. While they had not fought in a major conflict since 1830, many men had seen action along the border hunting brigands and criminals. Furthermore, advancement in the Hellenic Military was based primarily upon a man’s merit and achievements, meaning that Greece's military leaders were usually quite capable and talented commanders, unlike their aristocratic counterparts in the British military who were appointed based on their connections and wealth.

Finally, the Greek people had an intrinsically martial nature to them that had been exhibited with great effect during the Greek War of Independence nearly 30 years prior. Small bands of klephts and armatolis armed only with clubs, matchlock muskets, swords, and spears had successfully overcome much larger and much more modern armies of the Ottomans and Egyptians thanks to the ingenuity of their leaders and intricate knowledge of the local terrain. They were a hardy people willing to fight and die for their homeland, their kin, their honor, and their futures.

While the British and Ottomans could certainly defeat the Greeks in a pitched battle, the prospect of a prolonged occupation was clearly an unattractive prospect for London who envisioned a long and bitter guerilla war. There were also the political ramifications a war with Greece would entail for Britain as if they came to blows then and there, Westminster risked pushing Greece into the waiting arms of the Russian Empire forevermore, something that London was ill inclined to do. And yet, with the Greek people clamoring for war and the Ottoman Government showing little signs of facilitating the Greek partisan’s demands for independence, it would have appeared to all that war was an inevitability.

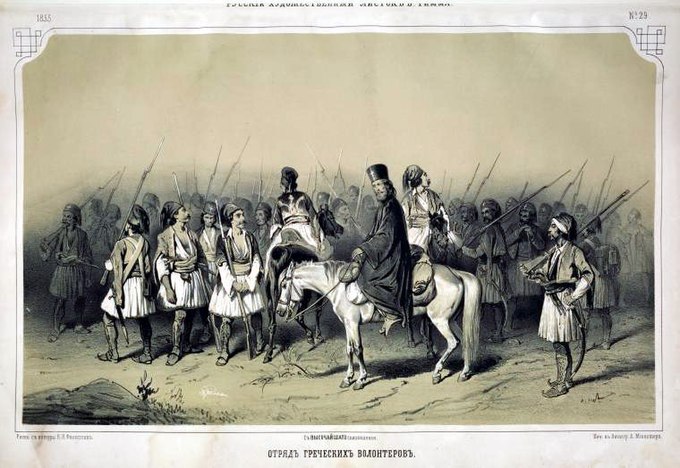

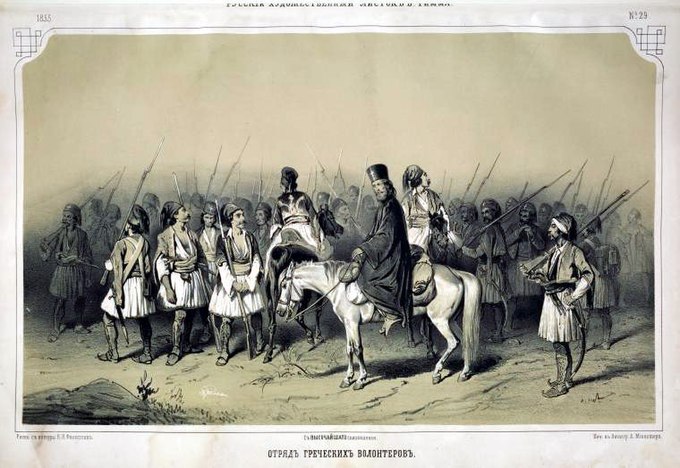

Volunteers from the Kingdom of Greece traveling to Thessaly

Despite his best efforts to maintain the peace, the anglophile King Leopold found himself increasingly isolated within the hawkish Greek Government. To refuse the Greek rebels aid in their struggle for liberty and independence would almost certainly destroy his legitimacy and support within the Kingdom of Greece, but to openly support them would risk war with his beloved niece Victoria’s homeland. To Leopold, Victoria was as near to him as his own beloved daughter Katherine, but more than that, she represented everything that he had once sought after in his youth. So, it came as no surprise that it was to Victoria that Leopold chose to confide in during the Summer months of 1854, calling upon her for help in averting this emerging crisis between their two countries.

Queen Victoria was quite sympathetic with her dear Uncle’s plight as she too wished to avoid strife between their two countries. However, she staunchly supported the war against Russia, having come to view Tsar Nicholas as an aggressive tyrant who would only be stopped by force of arms. More so, she could not show favoritism to any such figure, even her beloved uncle, especially when Leopold had gone to great lengths to ingratiate himself to the Russian Emperor over the past few years as doing so would call into question her own loyalties and whether they lay with her family or her country. Yet while she herself could offer no solution to this present crisis she would reach out to someone who could.

In late August 1854, on the precipice of war, the venerable statesman Lord Stratford Canning, 1st Baron Stratford de Redcliffe entered the debate. Lord Canning was a longtime supporter of the Greek people, having been one of the primary proponents of British intervention in the Greek War for Independence, and was among the most knowledgeable British statesmen on Greece. Owing to his role as British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Canning found himself in an increasingly prominent position within British politics once more, a position he had not been in since the days of his cousin George’s Premiership 25 years prior.

Taking it upon himself to pursue the British Empire’s interests in the Ottoman Empire - interests which now included maintaining the peace with Greece; Lord Canning would write to King Leopold and the Greek Government offering a deal. In return for the continued neutrality of the Kingdom of Greece in this present conflict between the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain and the Russian Empire; the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland would formally cede the Ionian Islands to Greece.

Located off the Western coast of mainland Greece, the Ionian Islands were a set of Greek islands stretching from the Southern cape of the Peloponnese to the coast of Epirus. Officially, the islands were an independent state, the United States of the Ionian Islands, but in truth they were another possession of the British Empire. Britain had acquired the islands from France during the Napoleonic Wars, using them as a naval base in the Eastern Mediterranean for many years. However, their value to London had diminished over the years, owing to the increased importance of Malta and burgeoning relations with Greece and the Ottoman Empire. Moreover, interest in the islands had been building in the neighboring Kingdom of Greece, which had been clamoring for the union of the Islands with Greece ever since they gained their independence in 1830.

Flag of the United States of the Ionian Islands

Many Greeks felt that Leopold, being a close friend of the British people, and the uncle of Britain’s future Queen, could beseech his beloved niece and her government to cede the islands to his new Kingdom as a show friendship and good faith between the two states. The Canningite Government for their part showed a great willingness to discuss the idea at the London Conference of 1830, with a tentative conference scheduled for early 1831. However, the revolutions in France, Italy and Belgium later that year would force Britain to delay these talks indefinitely until late 1832 following King Leopold’s marriage to Princess Marie of Württemberg. The Conference in the Fall of 1832 would begin well with diplomats discussing the possibility of ceding the islands to Greece in return for basing rights and other privileges for the British.

By this time however, George Canning lay on his deathbed and was forced to withdraw from government for the last time leaving the matter to his successor, the incredibly recalcitrant Duke of Wellington. Upon taking power, Wellington immediately nixed the discussion of trading the islands in the bud, effectively killing whatever momentum that had seemingly been building before Canning’s death. Wellington’s stance was continued by his successor the venerable Earl Grey, who had other, more important matters to attend to in the Americas and Asia. Even the succession of Leopold’s niece, Queen Victoria to the British throne in 1837 did little to move the matter in Greece’s favor as the islands remained stubbornly separate from the Greek state.

The Ionian Islands would only come to the fore of Anglo-Greek relations once more, following the Ionian revolt of 1848 and 1849 as the Eptanesians, inspired by the nationalistic zeal and revolutionary fervor of the Germans and Italians, began to advocate for greater ties to Greece. The ensuing British response resulted in numerous deaths, maimings, jailings, and exiles causing untold outrage throughout the Kingdom of Greece who felt betrayed by the British. While the unrest would eventually settle down, the tension between the two states did not. More than anything though, the Eptanesian Uprisings would succeed in bringing the issue to the fore once more.

Whether he was acting on his own volition, or acting under orders from London, none but Canning can truly say, but for an Ambassador of the British Empire to broach this topic to the Greek Government at this late hour was a totally unexpected, but not unwelcome development for both sides. It cannot be denied that the value of the islands had slowly diminished in London’s eyes, especially after the unrest of 1848 and 1849, but they could still provide some benefit in the present conflict. However, Canning almost certainly knew the value that the Greek Government placed on the Ionian Islands and sought to leverage this for as much as he could. Nevertheless, King Leopold and the “Peace Party” within the Greek Government immediately jumped at this opportunity and called for a halt to the Hellenic Military’s mobilization.

Lord Stratford Canning, 1st Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe circa 1860

The Vouli was at an impasse, however, as many were interested by Canning’s offer, yet many were not. Wishing to determine where the British Government stood on this issue, Prime Minister Kanaris dispatched his Deputy Prime Minister, Panos Kolokotronis to London to meet with Parliament and hear what they had to say on this matter. Arriving in London three weeks later, on the 1st of October, Kolokotronis together with the Greek Ambassador to Britain, Ioannes Adamos would meet with Parliament to discuss a potential work around to avoid war. To their delight, they would find that British Prime Minister Lord Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston and his Cabinet were quite receptive to a deal, likely owing to the recent reversals in the Balkans and Caucasia.

After some deliberation, Lord Palmerston and British Foreign Minister, Lord Clarendon called upon Kolokotronis and Adamos to propose their terms for a potential deal. If the Kingdom of Greece were to demobilize her forces and refrain from taking any hostile military action against the Ottoman Empire in this present conflict, then the British Empire would assent to the union of the Ionian Islands with the Kingdom of Greece. Moreover, they would also persuade the Sublime Porte of the Ottoman Empire to offer amnesty to the Greeks currently in revolt within their territories so long as they gave up their resistance against Konstantinyye.

While the offer of the Ionian Islands was certainly nice, Kolokotronis and Adamos believed that the deal was quite lacking, especially in the wake of Russian advances in the Caucasus. Moreover, the news from the Southern Balkans was also quite promising as Greek partisans were in control of most of Thessaly, large parts of Epirus, and a few isolated communities in Macedonia.[3] Several Greek freedom fighters had recently risen in revolt as well on the islands of Cyprus, Lesbos, Lemnos, and the Dodecanese Islands although the Ottoman authorities still controlled these islands officially.

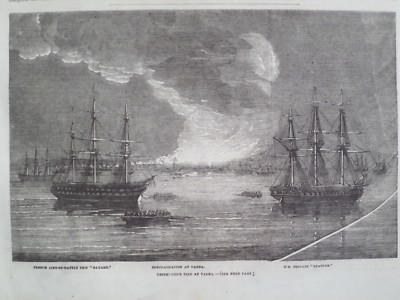

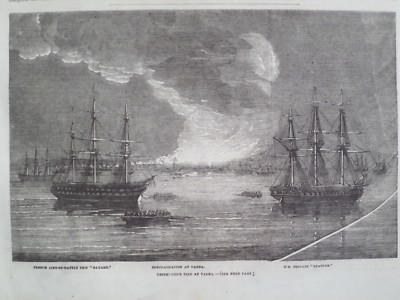

These developments would coincide with the burning of the Port of Varna in late October by Bulgarian and Greek arsonists within the city who supported the Russian Army. Although the British and Ottomans would react quickly with water pumps, nearly half the city was in ruins and the harbor was almost completely destroyed, forcing supplies and soldiers to offload at the port of Burgas roughly 70 miles to the South. Combined with a burgeoning Cholera pandemic within the Anglo-Ottoman camp at Silistra, the situation was looking rather bleak for the British Government in late 1854. As such, the Greek delegation deemed it necessary for the British to make further concessions to the Greeks in order to sweeten the deal. After some debate, the British Government would agree to support moderate revisions to the border between the Kingdom of Greece and the Ottoman Empire in Rumelia in addition to their previous concessions and a review of Greece’s ongoing debts. In return, Britain now asked for naval basing rights and logistical support for British forces in the region, both of which it promised to pay for with Gold Sterling.

The Varna Fire, 1854

Adamos and Kolokotronis would find these terms more to their liking and raced back to Athens to present the deal before the Vouli, but to their surprise the treaty would find a lukewarm response from the Legislature. All in attendance desired the Enosis of the Eptanesians with Greece, that was not in doubt, but the nebulous nature of the latter concession cast doubt over the entire deal. Moreover, several Representatives felt uneasy about aiding the British in their fight against the Russians in any capacity, while many thought that Greece could gain more by joining Russia rather than accept Britain’s “scraps”. Some even considered leveraging Greece’s support for the Russians as a means to pry further concessions from the British, however, this was made moot after Russia’s rather limited proposals to Greece became apparent - proposals limited to the Southern Aegean Islands and parts of Thessaly. After a week of heated debate and deliberation, Kanaris opted to put the resolution to a vote in the Vouli on the 26th of November.

As Representatives casts their votes one by one, the mood in the Vouli was decidedly dark as neither those who favored the deal, nor those in favor of war felt confident in their chances of success. On and on the procession of legislators went, like a black parade of mourners gathered for a funeral, until finally the last vote was cast. With great tribulation, Prime Minister Kanaris climbed the dais to recite the final tally of the vote. When the counting was finished, the total was 69 voting in favor of the deal with the British, 66 voting in opposition and 2 abstaining. The deal with Britain had passed and peace had carried the day in Greece by a razors margin. With that, the Greek Government and the British Government formally began negotiations over the transfer of the Ionian Islands to Greece.

Over the ensuing weeks, talks between Britain’s Lord Clarendon and Greece’s Panos Kolokotronis would flesh out the finer details of the agreement between their two countries. The Ionian Islands would be handed over to the Kingdom of Greece in one month’s time upon the official signing of the treaty on the 11th of February 1855. All fortifications and military installations across the islands would be preserved, but all munitions and weaponry would be returned to the British Empire. Britain would be granted unrestricted naval basing rights within the port of Corfu for 10 years, while the ports of Preveza, Patras, Piraeus, Heraklion, Chios, and Chania would provide access to British Warships for the duration of the present war with Russia.

The Kingdom of Greece would also be provided with favorable contracts to supply and service any British ship within Greek waters for the remainder of the conflict against Russia. To mollify particularly vocal Russophiles and Turkophobes within Greece, this would be limited purely to foodstuffs, medical services and supplies, and the repair of British ships, not the provision of military munitions or weapons. The Greek and British diplomats would also meet to redress the Greek debt held by the British Government, making slight revisions in Greece's favor. Finally, VP Psara (currently operating under the name HMS Mersey) would be sent to Greece within three months-time of the treaty’s official signing. While these developments were certainly not the preferred outcome for the Greeks, they were not the worst results either as the British were at least willing to pay for the services rendered to them by the Greeks.

The Clarendon-Kolokotronis Treaty – as it would later become known as - would begin the transition process for the Ionian Islands from British control to Greek. Over the course of the following weeks, British agents, politicians, and soldiers slowly departed from the islands after nearly fifty years in power. Finally, the United States of the Ionian Islands was officially dissolved on the 11th of March 1855 when its last Governor, Lord Barnhill formally departed Corfu for Malta. The union of the Ionian Islands with Greece was met with great ecstasy across Greece, as it represented the first real expansion of their state since the War of Independence. To some, however, the deal was not enough.

Many ardent nationalists and patriots felt spurned by the cheapness at which their government had been bought and denounced their government as weak and cowardly. Several hundred soldiers and sailors in the Hellenic Military would go even further, renouncing their commissions and oaths to the Greek State and departed to join Russia in her fight against the vile Ottomans. These men, known as the Hellenic Brigade, would fight alongside their Russian allies for the remainder of the Great Eurasian War, serving with great valor in the battles ahead. The agreement would also do little to calm the various Greek and Slavic rebels who continued to rise in revolt against their Ottoman overlords.

Greek Volunteers arriving in Russia

Helping sooth the anger of betrayal that many felt in Greece was the massive influx of British coin into Greek purses as part of the treaty. Irritatingly, the British would find the Greek ports lacking for the purposes of Warships. Thus, to meet their needs in the region, the British would be forced to loan heavily to the Greek Government in order to improve the development of these ports, modernizing and expanding them greatly. Piraeus in particular would receive special attention, as the British effectively sponsored the construction of a new careening dock and dry dock at the port. Perhaps the most important project that would see renewed work was the Corinth Canal.

Work had stalled on the project following a series of rock slides in 1854 that had killed several workers, which prompted a massive outpouring of public outrage and political repercussions that ultimately stalled the project indefinitely. For the next few months it would have appeared to all that the Corinth Canal was bound to be relegated to the dust bin of history, only it wasn't. Instead, the loss of two British ships (HMS Rodney and HMS Furious) as they rounded the dangerous Winter waters of the Peloponnese forced London to the board. Recognizing the strategic and financial benefits of the canal, the British would provide technical aid in the form of experienced canal engineers and some limited financial support by way of loans, prompting the Greek Government to restart work at the site in late 1855.

The matter of the border revisions with the Ottoman Empire were more contentious, however, as Britain supported relatively minor revisions to the Greek border in Central Greece, while the Greek Government demanded all of Thessaly, Epirus, Macedonia, the Aegean Islands, and Cyprus. This was certainly more than the British, let alone the Ottomans (who were not included in these preliminary talks) were willing to give. When they learned of these negotiations, the Sublime Porte immediately rejected any talks of conceding territory to the duplicitous Greeks who cravenly supported seditionists within the Empire, while simultaneously promising cooperation and good will. Yet with Russian Armies on the Southern bank of the Danube and in Eastern Anatolia, much of Southern Rumelia in open revolt, and London pressuring them to make a deal; the Porte had little choice in the matter if they wanted to keep Greece out of the war.

Lessening the blow was the fact that much of the territory in question, namely Epirus and Thessaly, were of limited value to the Ottoman Empire and were at present, largely outside of Kostantîniyye’s control. The Southern Aegean Islands, namely the Dodecanese Islands were of limited value to the Porte as well, given Greece’s control of Samos, Chios and Crete. However, the Porte vehemently opposed surrendering any part of Macedonia to the Greeks, which was of great value to the Empire and they also opposed surrendering the Northern Aegean Islands to the Greeks given their close proximity to the Straits. Moreover, the Albanians of Northern Epirus were strongly opposed to a Greek annexation of their lands and petitioned the Sultan to not concede their country to the Hellenes.

As debates between the Greeks, British, and Ottomans were taking place, an Ottoman Army under Veli Pasha advanced into Macedonia where it quickly subdued most of the rebel strongholds in the region. Although the Greeks would be enraged when they learned of the Ottoman suppression of their countrymen, Sultan Abdulmejid’s promise to offer amnesty to the remaining Greek rebels would quell this anger somewhat. After further negotiations with the British and Greeks; the Ottoman Government finally responded with a deal of its own. In return for continued Greek neutrality, the Sublime Porte of the Ottoman Empire would transfer control of the Dodecanese Islands to Greece in three months-time.

Additionally, should Greece remain neutral for the remainder of the current conflict against the Russian Empire and provide services to the British as laid out in the Clarendon-Kolokotronis Treaty, then the Ottoman Empire would also cede the lands of Thessaly (South of the Olympus Range) and Epirus (South and West of the Aoos River below Tepelenë ) to the Kingdom of Greece upon the conclusion of the present war. In addition to this was a clause requiring the Kingdom of Greece to renounce any further territorial claims on the Ottoman Empire and to refrain from offering any further support to brigands and seditionists within the Empire. While disappointing to some who had envisioned Greece gaining Macedonia, Cyprus, and the Northern Aegean Islands; the acquisition of Thessaly, Epirus and the Dodecanese Islands was still a great boon for the Kingdom of Greece at this time, and far better than initially expected. With few dissenting, Greece would accept the terms of the Treaty of Constantinople on the 8th of May 1855.

The annexation of the Dodecanese Islands three months later in August 1855 would help ease concerns in Greece as would the Ottoman Sultan’s promise of amnesty (provided they laid down their arms before the end of the year), but overall, the mood was quite mixed in Greece as a result of the Clarendon-Kolokotronis Treaty and the ensuing 1855 Treaty of Constantinople. Only upon the final annexation of Epirus and Thessaly in 1858 would the people of Greece truly come to appreciate their government’s decision. Nevertheless, the Kingdom of Greece would continue to abide by its agreement with Great Britain and the Ottoman Empire, providing a degree of comfort in London and Kostantîniyye for the duration of the war. And yet, as one threat to the Anglo-Ottoman Alliance was pacified, another threat soon emerged as on the 10th of November 1855, the Qajari Empire declared war on the Emirate of Afghanistan and Great Britain.

The Kingdom of Greece in 1858

Next Time: Swirling Sands

[1] Control of the sea is an incredibly important matter for Athens, as no community in Greece is further than 75 miles from the sea. Greece also possesses one of the longest coastlines in Europe despite its rather small size thanks in large part to the many islands and inlets under its control.

[2] A third Screw-Frigate, the Psara was ordered along with these two, but it was withheld by the British as the war with Russia broke out prior to its completion.

[3] This success was thanks in large part to the support of several rogue Hellenic Army officers and soldiers who had covertly crossed the border to support their countrymen in the preceding weeks and months.

Eptanisa joins Hellas

The start of the Great Eurasian War was met with great concern, but also great optimism by many within the Kingdom of Greece who saw this conflict as their best opportunity to liberate their kinsmen still under the Turkish yoke. This opinion was shared by many members of the Greek Government, especially those of the ruling Nationalist Party who openly called for war with the Ottoman Empire to liberate their countrymen and reclaim traditionally Greek lands from foreign oppression. Many Greeks also considered it their solemn duty to aid the Russians in their battle against the Turks, as Russia was their longtime friend and ally, while the Ottomans were their mortal enemy and ancient oppressor. However, Russia’s rather poor performance in the opening weeks of the war would quiet these calls for war within Athens, as many were unwilling to commit themselves to what appeared to be a losing effort.

Moreover, war with the Ottomans would have more dire consequences for Greece this time than a simple fight against the Turks, as Great Britain was formally allied with the Sublime Porte in its current struggle against Russia. Like Russia, Great Britain had been a stalwart friend and ally of Greece since 1827 and had become the country’s largest trade partner, consuming nearly half of all Greek exports by 1853. More than that though, Britain was the closest to Greece politically, as the Greek Constitution was heavily influenced by British liberalism, constitutional monarchism, and the rule of law.

Many prominent Britons, such as Lord George Byron, Lord Thomas Gordon, Lord Thomas Cochrane, and Lord Frank Abney Hastings had traveled to Greece during the Revolution to aid them in their struggle for independence, while others provided significant material and financial support from abroad. Lastly, Britain, alongside France and Russia, had intervened on behalf of the Greeks during the War of Independence, helping them win their independence in 1830. Beyond these feelings of fraternity and gratitude however, there was the existential threat that a hostile Britain would pose to Greece.

In terms of sheer numbers, the British Royal Navy vastly outmatched the Hellenic Royal Navy, outnumbering it and outgunning it in every regard, a fact which utterly terrified lawmakers in Athens. In the event of war between them, control of the sea would be lost to Britain almost immediately, which for a seafaring country such as Greece, would be a death sentence. With control of the seas lost, the mainland would be at risk and Athens would be within striking distance of an Anglo-Ottoman assault.[1] The Greek capital would almost certainly be occupied, their ports would be blockaded, their economy would be ruined, and their people would be oppressed. Nevertheless, a person in the throes of passion is rarely rationale, and with the war swing in favor of the Russians in late Summer - both in the Balkans and Caucasus, the Greeks began increasing their calls for war once more.

Tensions would be heightened in June, 1854 when nearly 40,000 Greeks rose in armed revolt across the Balkans demanding their independence from the Ottoman Empire and Enosis (Union) with the Kingdom of Greece. Distracted by the fighting along the Danube and in Eastern Anatolia, the Sublime Porte had few soldiers in place to police their Balkan territories, enabling the rebels to make rapid gains in the first few days. By the end of July, nearly all of Thessaly south of Larissa had been secured by the Greek revolutionaries, while large parts of Epirus from Paramythia and Tzoumerka to Himara and Argyrokastro had been taken by the rebels, including the provincial capital of Ioannina. The Greeks had less success in Macedonia and Thrace, only securing a few remote municipalities and communes such as Kastoria, Kozani, Xanthi, and Maroneia.

Faced with this great success, even the so-called moderate members of the Vouli began calling for armed intervention in the Ottoman Empire to aid their kinsmen. The matter was not helped by the Ottoman government who promptly dispatched whatever men and soldiers they could spare to contain the revolt, resulting in the brutal suppression of several Greek communities in Macedonia and Thrace. By July 1854, Prime Minister Constantine Kanaris was forced to act, officially mobilizing the Hellenic Military for war.

Greek Prime Minister Constantine Kanaris circa 1860

The mobilization of the Greek Military would not go unnoticed, however, as the British Government quickly learned of this development through their agents in Greece While the Greeks would pose little threat to the combined might of the British and Ottoman militaries, they would still be an unnecessary nuisance for them to deal with, especially with the war against Russia going worse than expected. On paper, the Hellenic Navy was rather small at only 47, mostly outdated ships. However, it featured a growing core of modern steam powered warships including a pair of brand-new Screw Frigates (VP Hydra and VP Spetsai), and four new screw corvettes (VP Miaoulis, VP Kanaris, VP Tombazis, and VP Ástinx (Hastings)).[2]

The Hellenic Navy could also be supplemented by hundreds of civilian vessels, ranging from small feluccas and xebecs armed only with muskets and swivel guns to larger brigs and sloops equipped with more powerful carronades and 24 pounders. However, the real potency of the Greek Navy lay in its sailors and officers who in all the world, were second only to the British in terms of skill and ability. Based on this, the Hellenic Navy and its auxiliaries would likely be great challenge to the Anglo-Ottoman Alliance, striking at their long and rather vulnerable supply lines throughout the Aegean from their numerous ports and coves with relative impunity.

The Hellenic Army was no slouch either. While it boasted a rather small standing army at only 18,000 men in peacetime - comparable to the initial British Expeditionary Army in 1854, it could quickly rise to 44,000 soldiers once its reservists were called to active service. An additional 34,000 men of the Ethnofylaki (the Hellenic National Guard) could be called up in a moment’s notice as well, boosting the total number of trained men to nearly 80,000 in theory. While they had not fought in a major conflict since 1830, many men had seen action along the border hunting brigands and criminals. Furthermore, advancement in the Hellenic Military was based primarily upon a man’s merit and achievements, meaning that Greece's military leaders were usually quite capable and talented commanders, unlike their aristocratic counterparts in the British military who were appointed based on their connections and wealth.

Finally, the Greek people had an intrinsically martial nature to them that had been exhibited with great effect during the Greek War of Independence nearly 30 years prior. Small bands of klephts and armatolis armed only with clubs, matchlock muskets, swords, and spears had successfully overcome much larger and much more modern armies of the Ottomans and Egyptians thanks to the ingenuity of their leaders and intricate knowledge of the local terrain. They were a hardy people willing to fight and die for their homeland, their kin, their honor, and their futures.

While the British and Ottomans could certainly defeat the Greeks in a pitched battle, the prospect of a prolonged occupation was clearly an unattractive prospect for London who envisioned a long and bitter guerilla war. There were also the political ramifications a war with Greece would entail for Britain as if they came to blows then and there, Westminster risked pushing Greece into the waiting arms of the Russian Empire forevermore, something that London was ill inclined to do. And yet, with the Greek people clamoring for war and the Ottoman Government showing little signs of facilitating the Greek partisan’s demands for independence, it would have appeared to all that war was an inevitability.

Volunteers from the Kingdom of Greece traveling to Thessaly

Despite his best efforts to maintain the peace, the anglophile King Leopold found himself increasingly isolated within the hawkish Greek Government. To refuse the Greek rebels aid in their struggle for liberty and independence would almost certainly destroy his legitimacy and support within the Kingdom of Greece, but to openly support them would risk war with his beloved niece Victoria’s homeland. To Leopold, Victoria was as near to him as his own beloved daughter Katherine, but more than that, she represented everything that he had once sought after in his youth. So, it came as no surprise that it was to Victoria that Leopold chose to confide in during the Summer months of 1854, calling upon her for help in averting this emerging crisis between their two countries.

Queen Victoria was quite sympathetic with her dear Uncle’s plight as she too wished to avoid strife between their two countries. However, she staunchly supported the war against Russia, having come to view Tsar Nicholas as an aggressive tyrant who would only be stopped by force of arms. More so, she could not show favoritism to any such figure, even her beloved uncle, especially when Leopold had gone to great lengths to ingratiate himself to the Russian Emperor over the past few years as doing so would call into question her own loyalties and whether they lay with her family or her country. Yet while she herself could offer no solution to this present crisis she would reach out to someone who could.

In late August 1854, on the precipice of war, the venerable statesman Lord Stratford Canning, 1st Baron Stratford de Redcliffe entered the debate. Lord Canning was a longtime supporter of the Greek people, having been one of the primary proponents of British intervention in the Greek War for Independence, and was among the most knowledgeable British statesmen on Greece. Owing to his role as British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Canning found himself in an increasingly prominent position within British politics once more, a position he had not been in since the days of his cousin George’s Premiership 25 years prior.

Taking it upon himself to pursue the British Empire’s interests in the Ottoman Empire - interests which now included maintaining the peace with Greece; Lord Canning would write to King Leopold and the Greek Government offering a deal. In return for the continued neutrality of the Kingdom of Greece in this present conflict between the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain and the Russian Empire; the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland would formally cede the Ionian Islands to Greece.

Located off the Western coast of mainland Greece, the Ionian Islands were a set of Greek islands stretching from the Southern cape of the Peloponnese to the coast of Epirus. Officially, the islands were an independent state, the United States of the Ionian Islands, but in truth they were another possession of the British Empire. Britain had acquired the islands from France during the Napoleonic Wars, using them as a naval base in the Eastern Mediterranean for many years. However, their value to London had diminished over the years, owing to the increased importance of Malta and burgeoning relations with Greece and the Ottoman Empire. Moreover, interest in the islands had been building in the neighboring Kingdom of Greece, which had been clamoring for the union of the Islands with Greece ever since they gained their independence in 1830.

Flag of the United States of the Ionian Islands

By this time however, George Canning lay on his deathbed and was forced to withdraw from government for the last time leaving the matter to his successor, the incredibly recalcitrant Duke of Wellington. Upon taking power, Wellington immediately nixed the discussion of trading the islands in the bud, effectively killing whatever momentum that had seemingly been building before Canning’s death. Wellington’s stance was continued by his successor the venerable Earl Grey, who had other, more important matters to attend to in the Americas and Asia. Even the succession of Leopold’s niece, Queen Victoria to the British throne in 1837 did little to move the matter in Greece’s favor as the islands remained stubbornly separate from the Greek state.

The Ionian Islands would only come to the fore of Anglo-Greek relations once more, following the Ionian revolt of 1848 and 1849 as the Eptanesians, inspired by the nationalistic zeal and revolutionary fervor of the Germans and Italians, began to advocate for greater ties to Greece. The ensuing British response resulted in numerous deaths, maimings, jailings, and exiles causing untold outrage throughout the Kingdom of Greece who felt betrayed by the British. While the unrest would eventually settle down, the tension between the two states did not. More than anything though, the Eptanesian Uprisings would succeed in bringing the issue to the fore once more.

Whether he was acting on his own volition, or acting under orders from London, none but Canning can truly say, but for an Ambassador of the British Empire to broach this topic to the Greek Government at this late hour was a totally unexpected, but not unwelcome development for both sides. It cannot be denied that the value of the islands had slowly diminished in London’s eyes, especially after the unrest of 1848 and 1849, but they could still provide some benefit in the present conflict. However, Canning almost certainly knew the value that the Greek Government placed on the Ionian Islands and sought to leverage this for as much as he could. Nevertheless, King Leopold and the “Peace Party” within the Greek Government immediately jumped at this opportunity and called for a halt to the Hellenic Military’s mobilization.

Lord Stratford Canning, 1st Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe circa 1860

The Vouli was at an impasse, however, as many were interested by Canning’s offer, yet many were not. Wishing to determine where the British Government stood on this issue, Prime Minister Kanaris dispatched his Deputy Prime Minister, Panos Kolokotronis to London to meet with Parliament and hear what they had to say on this matter. Arriving in London three weeks later, on the 1st of October, Kolokotronis together with the Greek Ambassador to Britain, Ioannes Adamos would meet with Parliament to discuss a potential work around to avoid war. To their delight, they would find that British Prime Minister Lord Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston and his Cabinet were quite receptive to a deal, likely owing to the recent reversals in the Balkans and Caucasia.

After some deliberation, Lord Palmerston and British Foreign Minister, Lord Clarendon called upon Kolokotronis and Adamos to propose their terms for a potential deal. If the Kingdom of Greece were to demobilize her forces and refrain from taking any hostile military action against the Ottoman Empire in this present conflict, then the British Empire would assent to the union of the Ionian Islands with the Kingdom of Greece. Moreover, they would also persuade the Sublime Porte of the Ottoman Empire to offer amnesty to the Greeks currently in revolt within their territories so long as they gave up their resistance against Konstantinyye.

While the offer of the Ionian Islands was certainly nice, Kolokotronis and Adamos believed that the deal was quite lacking, especially in the wake of Russian advances in the Caucasus. Moreover, the news from the Southern Balkans was also quite promising as Greek partisans were in control of most of Thessaly, large parts of Epirus, and a few isolated communities in Macedonia.[3] Several Greek freedom fighters had recently risen in revolt as well on the islands of Cyprus, Lesbos, Lemnos, and the Dodecanese Islands although the Ottoman authorities still controlled these islands officially.

These developments would coincide with the burning of the Port of Varna in late October by Bulgarian and Greek arsonists within the city who supported the Russian Army. Although the British and Ottomans would react quickly with water pumps, nearly half the city was in ruins and the harbor was almost completely destroyed, forcing supplies and soldiers to offload at the port of Burgas roughly 70 miles to the South. Combined with a burgeoning Cholera pandemic within the Anglo-Ottoman camp at Silistra, the situation was looking rather bleak for the British Government in late 1854. As such, the Greek delegation deemed it necessary for the British to make further concessions to the Greeks in order to sweeten the deal. After some debate, the British Government would agree to support moderate revisions to the border between the Kingdom of Greece and the Ottoman Empire in Rumelia in addition to their previous concessions and a review of Greece’s ongoing debts. In return, Britain now asked for naval basing rights and logistical support for British forces in the region, both of which it promised to pay for with Gold Sterling.

The Varna Fire, 1854

Adamos and Kolokotronis would find these terms more to their liking and raced back to Athens to present the deal before the Vouli, but to their surprise the treaty would find a lukewarm response from the Legislature. All in attendance desired the Enosis of the Eptanesians with Greece, that was not in doubt, but the nebulous nature of the latter concession cast doubt over the entire deal. Moreover, several Representatives felt uneasy about aiding the British in their fight against the Russians in any capacity, while many thought that Greece could gain more by joining Russia rather than accept Britain’s “scraps”. Some even considered leveraging Greece’s support for the Russians as a means to pry further concessions from the British, however, this was made moot after Russia’s rather limited proposals to Greece became apparent - proposals limited to the Southern Aegean Islands and parts of Thessaly. After a week of heated debate and deliberation, Kanaris opted to put the resolution to a vote in the Vouli on the 26th of November.

As Representatives casts their votes one by one, the mood in the Vouli was decidedly dark as neither those who favored the deal, nor those in favor of war felt confident in their chances of success. On and on the procession of legislators went, like a black parade of mourners gathered for a funeral, until finally the last vote was cast. With great tribulation, Prime Minister Kanaris climbed the dais to recite the final tally of the vote. When the counting was finished, the total was 69 voting in favor of the deal with the British, 66 voting in opposition and 2 abstaining. The deal with Britain had passed and peace had carried the day in Greece by a razors margin. With that, the Greek Government and the British Government formally began negotiations over the transfer of the Ionian Islands to Greece.

Over the ensuing weeks, talks between Britain’s Lord Clarendon and Greece’s Panos Kolokotronis would flesh out the finer details of the agreement between their two countries. The Ionian Islands would be handed over to the Kingdom of Greece in one month’s time upon the official signing of the treaty on the 11th of February 1855. All fortifications and military installations across the islands would be preserved, but all munitions and weaponry would be returned to the British Empire. Britain would be granted unrestricted naval basing rights within the port of Corfu for 10 years, while the ports of Preveza, Patras, Piraeus, Heraklion, Chios, and Chania would provide access to British Warships for the duration of the present war with Russia.

The Kingdom of Greece would also be provided with favorable contracts to supply and service any British ship within Greek waters for the remainder of the conflict against Russia. To mollify particularly vocal Russophiles and Turkophobes within Greece, this would be limited purely to foodstuffs, medical services and supplies, and the repair of British ships, not the provision of military munitions or weapons. The Greek and British diplomats would also meet to redress the Greek debt held by the British Government, making slight revisions in Greece's favor. Finally, VP Psara (currently operating under the name HMS Mersey) would be sent to Greece within three months-time of the treaty’s official signing. While these developments were certainly not the preferred outcome for the Greeks, they were not the worst results either as the British were at least willing to pay for the services rendered to them by the Greeks.

The Clarendon-Kolokotronis Treaty – as it would later become known as - would begin the transition process for the Ionian Islands from British control to Greek. Over the course of the following weeks, British agents, politicians, and soldiers slowly departed from the islands after nearly fifty years in power. Finally, the United States of the Ionian Islands was officially dissolved on the 11th of March 1855 when its last Governor, Lord Barnhill formally departed Corfu for Malta. The union of the Ionian Islands with Greece was met with great ecstasy across Greece, as it represented the first real expansion of their state since the War of Independence. To some, however, the deal was not enough.

Many ardent nationalists and patriots felt spurned by the cheapness at which their government had been bought and denounced their government as weak and cowardly. Several hundred soldiers and sailors in the Hellenic Military would go even further, renouncing their commissions and oaths to the Greek State and departed to join Russia in her fight against the vile Ottomans. These men, known as the Hellenic Brigade, would fight alongside their Russian allies for the remainder of the Great Eurasian War, serving with great valor in the battles ahead. The agreement would also do little to calm the various Greek and Slavic rebels who continued to rise in revolt against their Ottoman overlords.

Greek Volunteers arriving in Russia

Helping sooth the anger of betrayal that many felt in Greece was the massive influx of British coin into Greek purses as part of the treaty. Irritatingly, the British would find the Greek ports lacking for the purposes of Warships. Thus, to meet their needs in the region, the British would be forced to loan heavily to the Greek Government in order to improve the development of these ports, modernizing and expanding them greatly. Piraeus in particular would receive special attention, as the British effectively sponsored the construction of a new careening dock and dry dock at the port. Perhaps the most important project that would see renewed work was the Corinth Canal.

Work had stalled on the project following a series of rock slides in 1854 that had killed several workers, which prompted a massive outpouring of public outrage and political repercussions that ultimately stalled the project indefinitely. For the next few months it would have appeared to all that the Corinth Canal was bound to be relegated to the dust bin of history, only it wasn't. Instead, the loss of two British ships (HMS Rodney and HMS Furious) as they rounded the dangerous Winter waters of the Peloponnese forced London to the board. Recognizing the strategic and financial benefits of the canal, the British would provide technical aid in the form of experienced canal engineers and some limited financial support by way of loans, prompting the Greek Government to restart work at the site in late 1855.

The matter of the border revisions with the Ottoman Empire were more contentious, however, as Britain supported relatively minor revisions to the Greek border in Central Greece, while the Greek Government demanded all of Thessaly, Epirus, Macedonia, the Aegean Islands, and Cyprus. This was certainly more than the British, let alone the Ottomans (who were not included in these preliminary talks) were willing to give. When they learned of these negotiations, the Sublime Porte immediately rejected any talks of conceding territory to the duplicitous Greeks who cravenly supported seditionists within the Empire, while simultaneously promising cooperation and good will. Yet with Russian Armies on the Southern bank of the Danube and in Eastern Anatolia, much of Southern Rumelia in open revolt, and London pressuring them to make a deal; the Porte had little choice in the matter if they wanted to keep Greece out of the war.

Lessening the blow was the fact that much of the territory in question, namely Epirus and Thessaly, were of limited value to the Ottoman Empire and were at present, largely outside of Kostantîniyye’s control. The Southern Aegean Islands, namely the Dodecanese Islands were of limited value to the Porte as well, given Greece’s control of Samos, Chios and Crete. However, the Porte vehemently opposed surrendering any part of Macedonia to the Greeks, which was of great value to the Empire and they also opposed surrendering the Northern Aegean Islands to the Greeks given their close proximity to the Straits. Moreover, the Albanians of Northern Epirus were strongly opposed to a Greek annexation of their lands and petitioned the Sultan to not concede their country to the Hellenes.

As debates between the Greeks, British, and Ottomans were taking place, an Ottoman Army under Veli Pasha advanced into Macedonia where it quickly subdued most of the rebel strongholds in the region. Although the Greeks would be enraged when they learned of the Ottoman suppression of their countrymen, Sultan Abdulmejid’s promise to offer amnesty to the remaining Greek rebels would quell this anger somewhat. After further negotiations with the British and Greeks; the Ottoman Government finally responded with a deal of its own. In return for continued Greek neutrality, the Sublime Porte of the Ottoman Empire would transfer control of the Dodecanese Islands to Greece in three months-time.

Additionally, should Greece remain neutral for the remainder of the current conflict against the Russian Empire and provide services to the British as laid out in the Clarendon-Kolokotronis Treaty, then the Ottoman Empire would also cede the lands of Thessaly (South of the Olympus Range) and Epirus (South and West of the Aoos River below Tepelenë ) to the Kingdom of Greece upon the conclusion of the present war. In addition to this was a clause requiring the Kingdom of Greece to renounce any further territorial claims on the Ottoman Empire and to refrain from offering any further support to brigands and seditionists within the Empire. While disappointing to some who had envisioned Greece gaining Macedonia, Cyprus, and the Northern Aegean Islands; the acquisition of Thessaly, Epirus and the Dodecanese Islands was still a great boon for the Kingdom of Greece at this time, and far better than initially expected. With few dissenting, Greece would accept the terms of the Treaty of Constantinople on the 8th of May 1855.

The annexation of the Dodecanese Islands three months later in August 1855 would help ease concerns in Greece as would the Ottoman Sultan’s promise of amnesty (provided they laid down their arms before the end of the year), but overall, the mood was quite mixed in Greece as a result of the Clarendon-Kolokotronis Treaty and the ensuing 1855 Treaty of Constantinople. Only upon the final annexation of Epirus and Thessaly in 1858 would the people of Greece truly come to appreciate their government’s decision. Nevertheless, the Kingdom of Greece would continue to abide by its agreement with Great Britain and the Ottoman Empire, providing a degree of comfort in London and Kostantîniyye for the duration of the war. And yet, as one threat to the Anglo-Ottoman Alliance was pacified, another threat soon emerged as on the 10th of November 1855, the Qajari Empire declared war on the Emirate of Afghanistan and Great Britain.

The Kingdom of Greece in 1858

Next Time: Swirling Sands

[1] Control of the sea is an incredibly important matter for Athens, as no community in Greece is further than 75 miles from the sea. Greece also possesses one of the longest coastlines in Europe despite its rather small size thanks in large part to the many islands and inlets under its control.

[2] A third Screw-Frigate, the Psara was ordered along with these two, but it was withheld by the British as the war with Russia broke out prior to its completion.

[3] This success was thanks in large part to the support of several rogue Hellenic Army officers and soldiers who had covertly crossed the border to support their countrymen in the preceding weeks and months.

Last edited:

Gian

Banned

@Earl Marshal - So it's effctively a Hydra then. Cut off one head (Greece), and another (Persia) takes its place. They still haven't forgotten about Herat, after all.

BTW, I may decide to make a VT-BAM of all the territorial acquisitions Greece has since independence.

BTW, I may decide to make a VT-BAM of all the territorial acquisitions Greece has since independence.

Wow. Greece has just made out like a bandit. Not only has it greatly expanded its territory for essentially free, It has had Great Britain expand its ports and aid it in the construction of the Corinth canal. With all the wealth flowing in due to the supply deal alone, when Greece finally does get its hands on Thessaly, the money necessary to develop the region properly and fully integrate it may actually be available.

Lessening the blow was the fact that much of the territory in question, namely Epirus and Thessaly, were of limited value to the Ottoman Empire and were at present, largely outside of Kostantîniyye’s control. The Southern Aegean Islands, namely the Dodecanese Islands were of limited value to the Porte as well, given Greece’s control of Samos, Chios and Crete. However, the Porte vehemently opposed surrendering any part of Macedonia to the Greeks, which was of great value to the Empire and they also opposed surrendering the Northern Aegean Islands to the Greeks given their close proximity to the Straits. Moreover, the Albanians of Northern Epirus were strongly opposed to a Greek annexation of their lands and petitioned the Sultan to not concede their country to the Hellenes.

If I may, I'd strongly suggest for Epirus, Greece taking the area south and west of Aoos/Vjose river. This puts Himara, a Greek revolutionary hotbed since.. oh the 15th century and Argyrokastro in Greece avoiding future problems with Greek rebels, while leaving the eastern part on North Epirus like Korytza, which has the more pronounced Albanian population in the Ottoman empire. Border would be the one denoted in the map below as the US proposal in 1919, the one shown with ..__...__...__ in the map.

Arguably that's a win win situation, for both the Greeks and Ottomans. The Ottomans in effect lose little to nothing, Himara was either revolting or autonomous most of the time causing trouble, they show their Albanian subjects that they did support them, while the Greeks gain a town that politically is way more significant than its size would indicate given its revolutionary history and role in Greek education with the Akrokeraunian school created in 1779 and the earlier 1627 school. If you need a sweetener, there is Sason island which was part of the Ionian islands technically and can be left to the Ottoman empire...

This great update unleashed many butterflies, but one comes first in mind: In contrast to OTL 1881, Thessaly is overrun by armed Greek rebels. This is a Mothra size butterfly. In OTL, during the peaceful negotiations, the Ottoman landlords were selling their 400 chifliks to rich Greek diaspora capitalists. Said merchants and bankers saw the chifliks as just a safe investement. These absentee landowners didn't care to invest in their new properties and mechanize the production. Being powerful men, they formed a lobby that made the government impose tariffs in grain imports. Then, as they ensured their profits, they reduced the land assigned for grains and rented much of their property to semi-nomadic Sarakatsani and Vlachs for pasturage. It was an economic disaster.

The peasants themselves had it worse. Under ottoman law, they had at least the right to cultivate the land and it was difficult for an ottoman landlord to kick them out of their land. They also had ownership of their houses and of their tools. These privileges came from the old timariot system that it was quite feudal, with both the advantages and disadvantages. It can be argued that the final owner of the land was not the landlord but the ottoman state. The ottoman landlords, afraid that either the greek state would nationalize their chifliks or buy the land directly from the ottoman state, they rushed to sell. The diaspora Greek capitalists claimed that they bought everything, including the houses, tools and draft animals of the peasants. They enforced then their rule by armed gangs that terrorized the peasants of the 400 huge estates. This situation continued until the peasant rebellion in Kileler.

However, now the great difference is that we have armed peasants that have liberated their own villages and land. It is a totally different situation.

The greek state quickly recognized the value of Thessaly and did its best to develop infrastructure. Within 6 years of the annexation, 200 miles of railroad were laid along with the development of Volos as a major port. The only problem that didnt allow Thessaly to become a regional powerhouse in Greece was the landless peasant problem. The author has now almost solved the issue before it even arise. 36 years of misery are avoided and Thessaly can reach its potential.

The peasants themselves had it worse. Under ottoman law, they had at least the right to cultivate the land and it was difficult for an ottoman landlord to kick them out of their land. They also had ownership of their houses and of their tools. These privileges came from the old timariot system that it was quite feudal, with both the advantages and disadvantages. It can be argued that the final owner of the land was not the landlord but the ottoman state. The ottoman landlords, afraid that either the greek state would nationalize their chifliks or buy the land directly from the ottoman state, they rushed to sell. The diaspora Greek capitalists claimed that they bought everything, including the houses, tools and draft animals of the peasants. They enforced then their rule by armed gangs that terrorized the peasants of the 400 huge estates. This situation continued until the peasant rebellion in Kileler.

However, now the great difference is that we have armed peasants that have liberated their own villages and land. It is a totally different situation.

The greek state quickly recognized the value of Thessaly and did its best to develop infrastructure. Within 6 years of the annexation, 200 miles of railroad were laid along with the development of Volos as a major port. The only problem that didnt allow Thessaly to become a regional powerhouse in Greece was the landless peasant problem. The author has now almost solved the issue before it even arise. 36 years of misery are avoided and Thessaly can reach its potential.

Last edited:

That was certainly a nerve-wracking chain of events, so it's great to see Greece come out of this situation in a much better position. King Leopold's connections with Queen Victoria have borne fruit, and many other contributing factors like British war exhaustion and Greek rebellions have aligned to create the conditions necessary for these treaties as well. The territorial and economic acquisitions will certainly be of great benefit to the country, and may even lay the groundwork for future expansions also being achieved without getting dragged into a ruinous war. Due to the passionate attitudes of nationalism among many Hellenes in the region, achieving these objectives diplomatically is like walking on a razor's edge, but hopefully this example of success can be used to blunt that somewhat when similar situations occur in the future.

Last edited:

The greek state quickly recognized the value of Thessaly and did its best to develop infrastructure. Within 6 years of the annexation, 200 miles of railroad were laid along with the development of Volos as a major port. The only problem that didnt allow Thessaly to become a regional powerhouse in Greece was the landless peasant problem. The author has now almost solved the issue before it even arise. 36 years of misery are avoided and Thessaly can reach its potential.

Quite agree. Thessaly may have other of its OTL problems like malaria TTL, but at least the cifliks should be gone. After all this being 1854 there are also going to be a lot of pretty influential revolutionaries, like Odysseas Androutsos, in TTL still alive and almost certain to have crossed the border to join the rebels, and their children like Spyros Karaiskakis, the son of Georgios and a leader of the 1854 Thessalian revolt also pushing in the same direction. I don't think it was accidental that in OTL one of the leaders of the Thessalian peasants emancipation effort was non other than George Karaiskakis, the grandson of the revolutionary hero...

It is easier to deal with malaria than a few hundred powerful capitalists. What is mentionable is the fact that the Greek kingdom has already drained lake Copais and has the needed experience with similar hydraulic projects. The know-how is there.Thessaly may have other of its OTL problems like malaria TTL, but at least the cifliks should be gone.

Another thing I want to mention is that greek trade is skyrocketing. Greeks shipowners are ITTL in a much much better position, as they have been developing steamship fleets decades ahead of OTL. With the addition of the Dodecanese (and having already Chios, Samos and Crete), there are simply tens of thousands additional seamen compared to OTL. You dont find such human capital easily! It is possible that Greece has now more sailors than the Italian States and Austria combined!

If Greeks had controlled the East Med trade in OTL, now they are becoming a mercantile beast, having the British building their port infrastructure, with more capital, more sailors, more steamships and MUCH more industry compared to OTL.

Gian

Banned

I do have to ask @Earl Marshal how the new borders in Epirus/Thessaly looks like map-wise (or at least with some description of what it looks like.

Could anybody estimate the added population? I think it is 236,000 for the Ionian islands and around 250,000 for Thessaly. But what was the population of Epirus and the Dodecanese?

Thessaly has about 325-350.000 population,for the ionian islands you are correctCould anybody estimate the added population? I think it is 236,000 for the Ionian islands and around 250,000 for Thessaly. But what was the population of Epirus and the Dodecanese?

Due to the passionate attitudes of nationalism among many Hellenes in the region, achieving these objectives diplomatically is like walking on a razor's edge, but hopefully this example of success can be used to blunt that somewhat when similar situations occur in the future

Not sure it will work well, yeah the moderate will have plenty of argument due to how they get the butter and the money from the butter. (A french idiom difficult to translate something like they keep their cake they ate), and if they get a period of prosperity the complaints will start to fade. However, the peace was signed few months before Qajari Empire joined the war, nationalists and militarists will affirm that if the Greeks have joined the war with the help of Qajari a victory would have been likely. Egypt would have joined the war and due to the revolt, the skills of the Greek army, they could have won the war in a few months and free millions of Greece, making greek gains. They could say that the Greeks signed a favorable treaty because they pushed the king and the moderate to ask for more when they were promised an island and that these gains were due to their actions. It's easy to make history after the event happened, and the result of war could have been different, but with all the success enjoyed by the greeks many will become arrogant and start to believe that a victory would have been easy and that this peace treaty was a missed opportunity.

The Ottomans promised amnesty, but after the war they would treat the greeks with suspicions seeing them as greedy people that profited of the war to steal Ottomans lands and make a profit on their back, they will consider the wealth amassed by the greek as theft, they will see Greece with jealousy, and many Ottomans greek will be attracted by the Greece state causing the Ottoman to see and treat them as a fifth column, pushing the Greek nationalists to ask for their liberation.

Also, the Ottoman Empire is in a more desperate situation, and due to the fight that greek rebels put in difficulty the Ottoman empire (even if they only fight a few second rate troops). They will surely treat the ottoman army with condescension.

All of these ingredients are a recipe for disaster if the situation escalates out of control in the future, also after the war the Ottoman empire will be a wounded beast full of paranoia, i'm afraid that the situation will become difficult for many minorities after the war.

Ganishka

Banned

Its like asking a serial killer to vow he isn't going to kill anymore. But the Turks know the Greeks are not going to comply to this specific clause in the long term, they just want the legal moral ground when the next conflict with Greece comes.In addition to this was a clause requiring the Kingdom of Greece to renounce any further territorial claims on the Ottoman Empire and to refrain from offering any further support to brigands and seditionists within the Empire.

Now that was a MASSIVE gain for greece..they just increased by some 50 per cent and and additional 700k pop

Greek Thessalonika when? Still glad with what the Greeks got here. Almost doubled the size of their kingdom without firing a single shot. Can't wait to see more.

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan League

Share: